29 January - 4 February 1917

- By Mark Sutcliffe

- •

- 02 Feb, 2017

- •

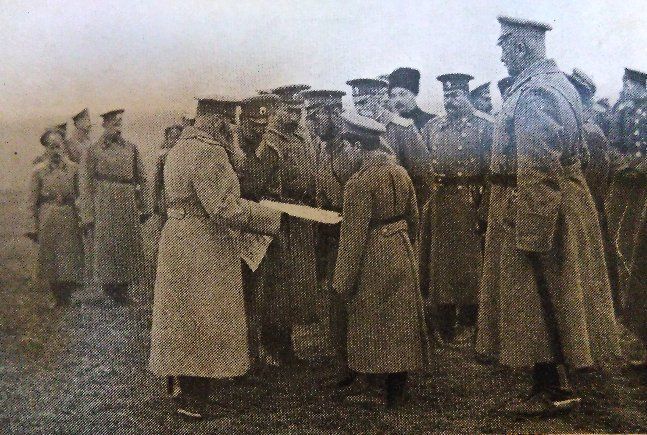

Spring 1916

(Major-General Sir Alfred Knox, With the Russian Army 1914-1917, London 1921)

29 January

Diary entry of Lev Tikhomirov, revolutionary and later conservative thinker

I’m worse again. Temperature’s gone up … In Moscow there’s a shortage of flour and bread. The city chief administrator has announced that his reserves have run out as well and asks the people to be patient. It wasn’t long – a week at most – since he was fining bakers for not requesting flour from his reserves! What a ridiculous situation. The bakers are calling him every name under the sun, saying that he’s bought up all the flour on the cheap and is now ‘giving it by the pood [16 kilos] to his cronies!’ I’m sick to death of all this. As though the chief administrator has thousands of cronies! A veritable tower of Babel. Meanwhile ‘the representatives of the allied nations’ are banqueting with representatives of our ‘society’ and making joint declarations about our impending victory. Milner [head of British delegation to Russia] has also been describing how the English will build up our industry. Of course they will, just as they’re doing in India!

(L.A. Tikhomirov, Diary 1915-1917, Moscow 2008)

Letter from Aleksei Peshkov [Maxim Gorky] to his wife E.P. Peshkova, from Petrograd

I very much advise against your coming here, Katia! … The situation is critical. If transport stops for two weeks, famine will set in. There’s already no flour here. The session of the Duma probably won’t open on the 14th, although all manner of turmoil could occur on that day … Things here in general are alarming and grim, and there would be nothing for you to do. I’m giving a reading on the first. It will be a success. Zinovii Peshkov [Gorky’s godson] has been promoted to lieutenant, he has been sent by the French to America and is getting forty dollars a day! He’s having an affair with Countess Chernikh, wife of the Sarajevan consul, the one who aided the Austrian plot against Serbia. The countess, who is English by birth, asked her husband for a divorce when the war began, and now Zinovii’s turned up! … Aleksei Peshkov is working like an ox. I’ve caught a cold, I’ve lost my voice, I’m sneezing, and I’m afraid that I won’t get better by the first! But that’s nothing! Everything here is abominable. I say this to you not by way of consolation, but just because that’s how it is.

Keep well!

A

(Maksim Gorky: Selected Letters, Oxford 1997)

Sunday Times article headed 'The Petrograd Conference: Russia's Peace Aims'

The Conference of the Allies in Petrograd is surrounded by mystery. Nothing official has transpired. However, it is an open secret that what the Conference is discussing is the future map of Europe. Everybody realises that the war has entered on its last stage. Everybody in Russia is confident of victory, even if to attain it a fight with the Government should become necessary.

(Sunday Times, 'From our own correspondent, Petrograd')

30 January

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

A meeting

with the Hermitage at 11, this time in the museum itself. All Hermitage people.

Everyone extremely pleasant to me, from the director Dm. Iv. Tolstoi down.

Seems they’ve decided to draw a veil over my article last year

[about poor

restoration of museum’s paintings]. Iskersky

[curator] once again revealed a

surprising degree of ignorance. The question of what to do with the large

paintings at Gatchina Palace was also discussed. They include a huge forest

landscape with figures, showing the ‘Flight into Egypt’ (Lipgart

[curator of

paintings] claims that it’s an early Titian! I’m more inclined to attribute it

to Domenico Campagnola) … These paintings were taken to the Hermitage

temporarily for restoration, but they would like to ‘incorporate’ them. Will

the Dowager Empress

[Maria Feodorovna] agree to this? After all, she is

fundamentally opposed to any changes to Gatchina’s artistic ensemble: ‘As it

was under the late Sovereign, so it must remain!’ … Lunched with Argutinsky

[collector] at Café Donon. Two of our elegant diplomats – Savinsky and Prince

Urusov – came and sat with us. This quite spoilt it for me, as they blathered

on the whole time, either about the war, or mutual acquaintances, or about the

Allies. And a table away from us were two of the most typical Jews imaginable,

with predatory faces, discussing with gusto their (no doubt dark) affairs. It

seemed very clear who now holds the cards, who is generally ‘master of the

situation’, and into whose hands the present critical state of affairs will

play.

(Alexander Benois,

Diary 1916-1918, Moscow 2006)

31 January

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

Eleven workmen,

members of the Central Committee of Military Industries, have just been

arrested on a charge of ‘plotting a revolutionary movement with the object of

proclaiming a republic’. Arrests of this kind are common enough in Russia, but

in the ordinary way the public hears nothing about them. After a secret trial,

the accused are sent to a state gaol or banished to the depths of Siberia. The

press never mentions the matter, and quite frequently even their families do

not know what has happened to their missing relative. The silence in which

these summary convictions are wrapped has a good deal to do with the tragic

notoriety of the

Okhrana. But this

time the element of mystery has been dispensed with. A sensational communiqué informs the press of the

arrest of the twelve workmen. This is Protopopov’s way of showing how busy he

is in saving tsarism and society.

(Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs 1914-1917, London 1973)

1 February

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

Visit from

Scamoni

[printer] again. He is convinced there won’t be any serious

disturbances, only some isolated and fruitless strikes resulting from specific

harassment of workers. But he’s basing his judgement on the business he runs –

and the Golike-Vyborg printing house is run on far more cultured lines than

many other, bigger enterprises. Their workers, it seems, are happy with their

situation, which has greatly improved in recent times. ‘Their doorkeeper now

earns more than the typesetter used to’.

(Alexander Benois,

Diary 1916-1918, Moscow 2006)

2 February

Diary entry of James L. Houghteling, Jr, attaché at the American Embassy, Petrograd

This is a

church holiday, and G. and I went out to Lyubertsi, the Harvester Company’s

industrial town ten miles out, to ski with the Varkalas … The travelling was

up-hill and down-dale but the snow was fairly hard and the air clear and

exhilarating. We came to no fences nor boundary marks till we neared the

monastery … After an hour we came out on the top of steep slopes above the

valley of the Moskva River … Here we had glorious coasting, so good that we

climbed up and tried again. On the second trip down, I carelessly raised one

foot and had the pleasure of seeing my ski dash off down the hill ahead of me.

Of course I had a beautiful fall and the rest of the slide was a mélange of

hopping, tripping and bad language.

(James L. Houghteling, Jr, A Diary of the Russian Revolution, New York 1918)

4 February

Letter from Nicholas II to his cousin George V

My dearest Georgie,

I thank you very much for your kind long letter. I entrust mine to the care of Lord Milner, whose acquaintance I was very pleased to make. Twice I had the occasion of seeing all the members of your mission. I hope they will return safely to England – the journey has become now still more risky since those d--d pirates sink every ship they can only get hold of. In a couple of days the work of the Conference will come to an end. May its results be fruitful and of useful consequences for both our countries and for all the Allies. The weak state of our railways has since long preoccupied me. The rolling stock has been and remains insufficient and we can hardly repair the worn out engines and cars, because nearly all the manufactories and fabrics of the country work for the army. That is why the question of transport of stores and food becomes acute, especially in winter, when the rivers and canals are frozen. Everything is being done to ameliorate this state of things which I hope will be overcome in April. But I never lose courage and egg on the ministers to make them and those under them work as hard as they can. But whatever the difficulties may be yet in store for us – we shall go on with this awful war to the end.

Alix and I send May and your children our fond love.

With my very best wishes for your welfare and happiness. Ever my dearest Georgie, your most devoted cousin and friend,

Nicky

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion, London 1996)

Diary entry of Lev Tikhomirov, revolutionary and later conservative thinker

Moscow is

dark, they’re not lighting the lamps. So of course the robbers are having a

field day. What a difficult time! It’s not just the maid who’s barely

surviving, even the cat Barsik has got as thin as a skeleton. There’s nothing

to eat – he eats potato. Today I gave Masha 40 kopecks to buy him some offal.

He loves it but when there’s nothing to buy, there’s nothing to give him. He’s

already polished off every mouse going. Poor old cat.

(L.A. Tikhomirov, Diary 1915-1917, Moscow 2008)

4 February 2017

A review in the Guardian of the Royal Academy's Revolution exhibition that's due to open next weekend. In fact the article takes issue with the title rather than the exhibition, which the reviewer hasn't yet seen, and whether it's right to be celebrating revolutionary art in this way – art that glorifies the victory of a regime achieved through terrible bloodshed. Not sure I agree with the premise, but it got me thinking about contemporary Russian or earlier Soviet attitudes to the seismic events of 1917. It's easy (particularly for students of Russian art and literature) to be misty-eyed about a revolution that forged the work of poets and artists such as Mayakovsky, Stepanova and Rodchenko in its fire; less so perhaps for those who lived with the consequences. Dmitry Furman, who died in 2011, has been described as 'a scholar ... who joined political integrity and intellectual originality in a body of work that addressed the fate of his country, and the past of the world, in ways that were equally and strikingly passionate and dispassionate'. In response to the 'what ifs', the different paths Russia could have taken in the early twentieth century, Furman wrote this: 'This was, in the end, our revolution, engendered by our culture. In countries with a cultural tradition such as that of England, the USA or the Netherlands, this kind of revolution would be essentially impossible. With us, though, powerful forces were pushing us towards it, forces linked to internal cultural factors that were specifically ours: the cultural rift between the top and bottom of society; the 'westernized' orientation of the intelligentsia and its desire ... not just to catch up with the West but surpass it and make Russia the lodestar for the whole world; the inflexibility of a political and ideological structure that made gradual, evolved development almost impossible; and the archaic mindset of the popular masses, who could only grasp revolutionary ideology in a quasi-religious form. Maybe there could have been other other ways, perhaps less bloody, perhaps more so, but to imagine that if 1917 hadn't happened Russia would have developed peacefully and quickly, and would now be some kind of USA-equivalent – it's virtually impossible.'

8 October

Letter from Lenin to the Bolshevik Comrades attending the Regional Congress of

the Soviets of the Northern Region

Comrades, Our revolution is passing through a highly critical period …

A gigantic task is being imposed upon the responsible leaders of our Party,

failure to perform which will involve the danger of a total collapse of the

internationalist proletarian movement. The situation is such that verily,

procrastination is like unto death … In the vicinity of Petrograd and in

Petrograd itself — that is where the insurrection can, and must, be decided on

and effected … The fleet, Kronstadt, Viborg, Reval, can and must advance

on Petrograd; they must smash the Kornilov regiments, rouse both the capitals,

start a mass agitation for a government which will immediately give the land to

the peasants and immediately make proposals for peace, and must overthrow

Kerensky’s government and establish such a government. Verily, procrastination

is like unto death.

(V.I. Lenin and Joseph Stalin, The Russian Revolution: Writings and Speeches

from the February Revolution to the October Revolution, 1917, London 1938)

9 October

Report in The Times

The Maximalist [Bolshevik], M. Trotsky, President of the Petrograd Soviet,

made a violent attack on the Government, describing it as irresponsible and

assailing its bourgeois elements, ‘who,’ he continued, ‘by their attitude are

causing insurrection among the peasants, increasing disorganisation and trying

to render the Constituent Assembly abortive.’ ‘The Maximalists,’ he declared,

‘cannot work with the Government or with the Preliminary Parliament, which I am

leaving in order to say to the workmen, soldiers, and peasants that Petrograd,

the Revolution, and the people are in danger.’ The Maximalists then left the

Chamber, shouting, ‘Long live a democratic and honourable peace! Long live the

Constituent Assembly!’

(‘Opening of Preliminary Parliament’, The Times)

10 October

As Sukhanov left his home for the Soviet on the morning of the 10th, his

wife Galina Flakserman eyed nasty skies and made him promise not to try to

return that night, but to stay at his office … Unlike her diarist husband,

who was previously an independent and had recently joined the Menshevik left,

Galina Flakserman was a long-time Bolshevik activist, on the staff of Izvestia.

Unbeknownst to him, she had quietly informed her comrades that comings and

goings at her roomy, many-entranced apartment would be unlikely to draw

attention. Thus, with her husband out of the way, the Bolshevik CC came

visiting. At least twelve of the twenty-one-committee were there … There

entered a clean-shaven, bespectacled, grey-haired man, ‘every bit like a

Lutheran minister’, Alexandra Kollontai remembered. The CC stared at the

newcomer. Absent-mindedly, he doffed his wig like a hat, to reveal a familiar

bald pate. Lenin had arrived.

(China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution, London 2017)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai

Sukhanov

Oh, the novel jokes of the merry muse of History! This supreme and decisive

session took place in my own home … without my knowledge … For such a

cardinal session not only did people come from Moscow, but the Lord of Hosts

himself, with his henchman, crept out of the underground. Lenin appeared in a

wig, but without his beard. Zinoviev appeared with a beard, but without his

shock of hair. The meeting went on for about ten hours, until about 3 o’clock

in the morning … However, I don’t actually know much about the exact

course of this meeting, or even about its outcome. It’s clear that the question

of an uprising was put … It was decided to begin the uprising as quickly

as possible, depending on circumstances but not on the Congress.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record, Oxford 1955)

11 October

British Consul Arthur Woodhouse in a letter home

Things are coming to a pretty pass here. I confess I should like to be out

of it, but this is not the time to show the white feather. I could not ask for

leave now, no matter how imminent the danger. There are over 1,000 Britishers

here still, and I and my staff may be of use and assistance to them in an

emergency.

(Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917, London 2017)

Memoir of Fedor Raskolnikov, naval

cadet at Kronstadt

The proximity of a proletarian rising in Russia, as prologue to the world

socialist revolution, became the subject of all our discussions in

prison … Even behind bars, in a stuffy, stagnant cell, we felt instinctively

that the superficial calm that outwardly seemed to prevail presaged an

approaching storm … At last, on October 11, my turn [for release]

came … Stepping out of the prison on to the Vyborg-Side embankment and

breathing in deeply the cool evening breeze that blew from the river, I felt

that joyous sense of freedom which is known only to those who have learnt to

value it while behind bards. I took a tram at the Finland Station and quickly

reached Smolny … In the mood of the delegates to the Congress of Soviets

of the Northern Region which was taking place at that time .. an unusual

elation, an extreme animation was noticeable … They told me straightaway

that the CC had decided on armed insurrection. But there was a group of

comrades, headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev, who did not agree with this decision

and regarded a rising a premature and doomed to defeat.

(F.F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917, New York 1982, first

published 1925)

12 October

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to Russia

On [Kerensky] expressing the fear that there was a strong anti-Russian

feeling both in England and France, I said that though the British public was

ready to make allowances for her difficulties, it was but natural that they

should, after the fall of Riga, have abandoned all hope of her continuing to

take an active part in the war … Bolshevism was at the root of all the

evils from which Russia was suffering, and if he would but eradicate it he

would go down to history, not only as the leading figure of the revolution, but

as the saviour of his country. Kerensky admitted the truth of what I had said,

but contended that he could not do this unless the Bolsheviks themselves

provoked the intervention of the Government by an armed uprising.

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia, London 1923)

13 October

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Kerensky is becoming more and more unpopular, in spite of certain grotesque

demonstrations such as this one: the inhabitants of a district in Central

Russia have asked him to take over the supreme religious power, and want to

make him into a kind of Pope as well as a dictator, whereas even the Tsar was

really neither one nor the other. Nobody takes him seriously, except in the

Embassy. A rather amusing sonnet about him has appeared, dedicated to the beds

in the Winter Palace, and complaining that they are reserved for hysteria

cases … for Alexander Feodorovich (Kerensky’s first names) and then

Alexandra Feodorovna (the Empress).

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917–1918, London 1969)

14 October 2017

The BBC2 semi-dramatisation of how the Bolsheviks took power, shown this week,

was a curious thing. Talking heads in the form of Figes, Mieville, Rappaport,

Sebag-Montefiore, Tariq Ali, Martin Amis and others were interspersed with

moody reconstructions of late-night meetings, and dramatic moments such as

Lenin’s unbearded return to the Bolshevik CC (cf Sukhanov above). The programme

felt rather staged and unconvincing, with a lot of agonised expressions and

fist-clenching by Lenin, but the reviewers liked it. Odd, though, that

Eisenstein’s storming of the Winter Palace is rolled out every time, with a

brief disclaimer that it’s a work of fiction and yet somehow presented as

historical footage. There’s a sense of directorial sleight of hand, as if the

rather prosaic taking of the palace desperately needs a re-write. In some

supra-historical way, Eisenstein’s version has become the accepted version.

John Reed’s Ten Days that Shook the World

, currently being

serialised on Radio 4, is also presented with tremendous vigour, and properly

so as the book is nothing if not dramatic. Historical truth, though, is often

as elusive in a book that was originally published — in 1919 — with an

introduction by Lenin. ‘Reed was not’, writes one reviewer, ‘an ideal observer.

He knew little Russian, his grasp of events was sometimes shaky, and his facts

were often suspect.’ Still, that puts him in good company, and Reed is

undoubtedly a good read.