8-14 January 1917

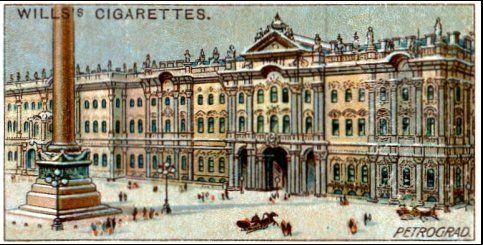

Cigarette cards, known as 'stiffeners' because they stiffened the paper cigarette packets and protected their contents, were popular throughout the war but production stopped in 1917 due to paper shortages.

An immense inter-Allied delegation, composed of high-ranking ministers and senior generals, arrived in Russia. It brought to the Russian people the hope that by some last-minute action the fallen fortunes of Russia might be repaired. The delegation visited both St Petersburg and Moscow. It suffered endless entertainment. Patiently it took reams of evidence. It listened to all, but mainly to the 'high-ups' in St Petersburg. In the end it decided that there would be no revolution.

(Robert Bruce Lockhart, Foreign Affairs

journal 1957)

At the beginning of 1917, blizzards and plummeting temperatures cut supplies and drove prices higher still, until the cost of a loaf of bread was rising at the rate of two percent a week. The price of potatoes and cabbage rose at a weekly rate of three percent, sausage at seven percent, and sugar at more than ten ... That the city's masses were angry and restless was an open secret, and the reasons were painfully obvious. 'Children are starving,' a secret police agent reported. 'A revolution, if it takes place ... will be spontaneous, quite likely a hunger riot.' 'Every day,' another added, 'the masses are becoming more and more embittered. An abyss is opening between them and the government.'

(W. Bruce Lincoln, Sunlight at Midnight

, New York 2000)

8 January

Tsar's message to his people

In complete solidarity with our faithful Allies, not entertaining any thought of a conclusion of peace until final victory has been secured, I firmly believe that the Russian people, supporting the burden of war with self-denial, will accomplish their duty to the end, not stopping at any sacrifice.

('The Tsar's rescript': a message from Nicholas II on 8 January, reported in The Times

on 9 (22) January)

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

The Emperor has told his aunt, the Grand Duchess Vladimir, that in their own interests his cousins, the Grand Dukes Cyril and Andrew, should leave Petrograd for a few weeks.

(Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs 1914-1917

,

London 1973)

Newspaper response to 'The Tsar's rescript'

The

patriotic enthusiasm which the nation manifested at the beginning of the war

and all the practical demonstrations of this spirit displayed in the public

efforts to develop the supply of munitions and in every way to cooperate with

the Army have merely been intimidated by order of the bureaucracy, which saw in

them a danger to its monopoly of the Government. The estrangement between the

Government and public opinion was bound to react upon the spirit of the nation.

Popular enthusiasm quickly subsided and in the place of the union of all forces

in the country so joyfully heralded in the earlier stages of the war, we had to

note a deplorable widening of the breach between the nation and its rulers. The

whole country watches this process with the bitterest feelings. We are as far

as ever from the union of all for the war and from the victory that we see

realized by our Allies.

( Novoe Vremya

, as reported in The Times

on 8 (21) January)

9 January

On 9 January

1917, the Workers Group of the War Industries Committee chose to mark the

anniversary of Bloody Sunday (a massacre that had sparked off the 1905

Revolution) with a massive strike in the capital. Forty per cent of Petrograd’s

industrial workforce took part. The Minister of the Interior, Alexander

Protopopov (1866-1918), ordered the arrest of the leaders and stationed Cossack

troops in the city.

Lecture by Lenin to an audience of young workers in Zurich

We the old shall perhaps not live to see the decisive battles of this coming revolution. But I believe I can express with some confidence the hope that the youth, which is working so splendidly in the socialist movement of Switzerland and of the whole world, will be fortunate enough not only to fight, but also to win in the coming proletarian revolution.

(James D. White, 'Lenin, the Germans and the February Revolution', Revolutionary Russia

1992)

10 January

Diary entry of Olga, eldest daughter of Nicholas and Alexandra

We 2 with Mama went to visit the grave of Father Grigori [Rasputin]. Today is his name day. Had a music lesson with T. In the evening Papa read to us, Chekhov's 'Sobytie' [The Incident] and started 'Vragi' [The Enemy].

( The Diary of Olga Romanov

, Yardley 2014)

12 January

Diary entry of Lev Tikhomirov, revolutionary and later conservative thinker

What a detestable time Russia is going through! The people are generally in an extreme state of nerves and despair of any hopeful resolution. The papers still write of victory, but nobody believes that in truth. The government has lost every last bit of credibility, not to mention respect. And finally people no longer believe each other, everyone thinks they are surrounded by scoundrels.

(L.A. Tikhomirov, Diary 1915-1917

, Moscow 2008)

I have found a solution for the perplexing problem of talking to the servants in this hotel. The chambermaid is an amusing old dame from the Baltic provinces, as quick as a steel trap, and talks German fluently. By much gesticulation and pointing I can make her understand me in that tongue and she tells me the Russian words which I immediately hunt up in my dictionary, to make sure of their spelling ... After dinner tonight, old Mr P - of Boston dropped in to borrow some books. We chatted and our talk soon turned to Rasputin, a never-failing topic these days. He remarked with true New England disgust that Rasputin was the most immoral man in Russia; and a man of tremendous magnetic and physical powers. He has heard that the reason for the murder was not politics but involved an intimacy between the self-styled monk and the wife of one of the high persons implicated. At any rate, Rasputin was invited to 94 Moika, Prince Yussupoff's house, was met there by his host, with the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Purishkevich, and others, and after some preliminaries was ordered to commit suicide. When he refused, one of them, reputedly Purishkevich, took the pistol and shot him. His body was taken across the Islands and dropped off one of the far bridges through a hole in the ice. The rope and weight slipped off, so that the corpse floated and was found. Armour tells me that a few days afterwards he drove across the same bridge and that his driver pointed out the hole, crossed himself and said, 'It has not frozen; he was a saint!'

(James L. Houghteling, Jr, A Diary of the Russian Revolution , New York 1918)

13 January

The writer Stepan Skitalets writes in a Moscow paper

About a verst (one kilometre) from the Senate and museums the twentieth century immediately turns into the seventeenth, and for the moment they don't notice this but at some point they will reap the fruits of this blindness and neglect. Possibly far sooner than they think.

(Skitalets [S.G. Petrov], Rannee utro , 13 January 1917)

New York at that moment lived like no other place on earth. Certainly not Europe. Europe in January 1917 remained trapped in a slow motion agonizing hell. The world war had entered its third year, having already killed more than ten million soldiers and civilians. France and England, Russia and Germany, Austria and Turkey; each would lose a million young men or more ... Amid all the noise that Saturday night, January 13, 1917, a few people knew that Leon Trotsky was coming. Trotsky was a celebrity in some circles. One small Russian-language newspaper called Novy mir (New World), published in Greenwich Village, proudly touted its connection to a small international band of Russian leftists calling themselves Bolsheviks or Mensheviks, depending on who controlled the editorial desk that week. It claimed Trotsky as one of its own and had announced his travel plans on its front page.

(Kenneth D. Ackerman, Trotsky in New York, 1917 (Berkeley, CA 2016)

[Trotsky] rented a three-room apartment in the Bronx which, though cheap by American standards, gave him the unaccustomed luxuries of electric light, a chute for garbage and a telephone. Later there were legends that Trotsky had worked in New York as a dish-washer, as a tailor, and even as an actor. But in fact he scraped a living from émigré journalism and lecturing to half-empty halls on the need for world revolution. He ate in Jewish delicatessens and made himself unpopular with the waiters by refusing to tip them on the grounds that it was injurious to their dignity. He bought some furniture on an instalment plan, $200 of which remained unpaid when the family left for Russia in the spring. By the time the credit company caught up with him, Trotsky had become Foreign Minister of the largest country in the world.

(Orlando Figes, A People's Tragedy , London 1996)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

14 January 2017

Some other events to mark the anniversary:

The Cambridge Courtauld Russian Art Centre (CCRAC) is organising a conference linked to the Art born in the revolution exhibition at the RA on 24-25 February.

From 4 February to 17 September The Hermitage Amsterdam will host an exhibition of items relating to the reign and demise of Nicholas II, and his family. The exhibits are from the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, and the State Archive of the Russian Federation, Moscow.

Tate Modern is exhibiting its collection of posters, photographs and other graphic works from the David King Collection in an exhibition called Red Star over Russia , opening in November.