14-20 May 1917

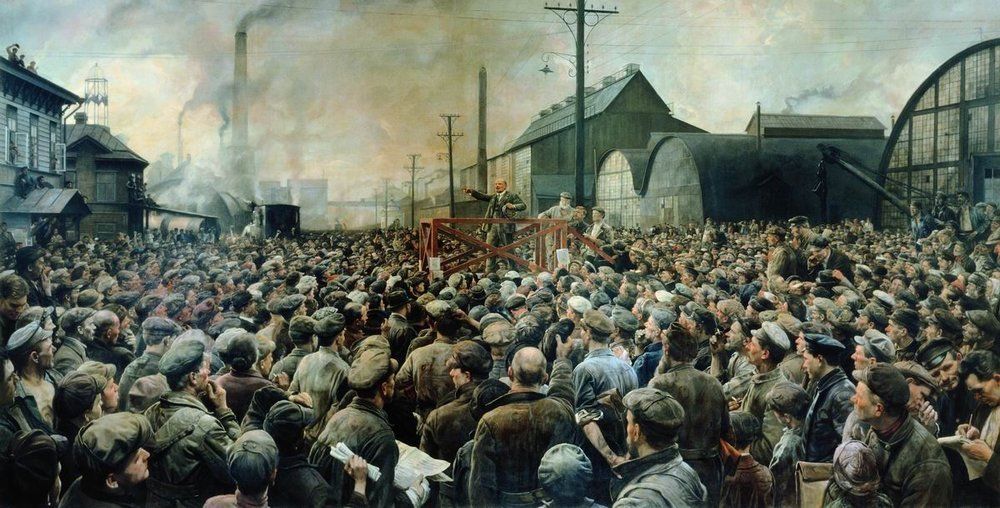

Lenin speaking to the workers of the Putilov Factory, 1917. Painting by Isaak Brodsky

Factory workers now began to shift their loyalties from unions organised horizontally, along professional lines, to those organised vertically, by enterprises. This development promoted syndicalism, a form of anarchism that called for the abolition of the state and for worker control of the national economy ... Lenin now identified himself with syndicalism, joining calls for 'worker control' of industry. This gained for his party a strong following among industrial workers: at the First Conference of Petrograd Factory Committees at the end of May, the Bolsheviks controlled at least two-thirds of the delegates.

(Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution

, London 1995)

14 May

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov

On May 14th Kerensky published an Order to the army –

concerning an offensive … ‘In the name of the salvation of free Russia, you

will go where your commanders and your Government send you. On your

bayonet-points you will be bearing peace, truth and justice. You will go

forward in serried ranks, kept firm by the discipline of your duty and your

supreme love for the revolution and your country.’ The proclamation was written

with verve and breathed sincere ‘heroic’ emotion. Kerensky undoubtedly felt

himself to be a hero of 1793. And he was of course equal to the heroes of the

great French Revolution, but – not of the Russian.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record

, Oxford 1955)

15 May

Appeal by the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’

Deputies to the Socialists of all Countries

Comrades: The Russian Revolution was born in the fire of the

world war. This war is a monstrous crime on the part of the imperialists of all

the countries, who, by their lust for annexations, by their mad race of

armaments, have prepared and made inevitable the world conflagration … Let the

movement for peace, started by the Russian Revolution, be brought to a

conclusion by the efforts of the International Proletariat.

( Russian-American Relations March 1917-March 1920

, New York 1920)

16 May

Extract from the Cologne Gazette

We must be quite clear about the fact that, if the Russian

chooses the Englishman as his friend, the world-power of Germany is relegated

to a misty distance; it is, indeed, doubtful whether in that event, our object

can ever be achieved. Moreover, in addition to this loss, we shall have for a

long time to come to reckon with Continental struggles which will cost blood,

money and strength.

The Times, ‘Ways to World-Power’, Through German Eyes, The

Times

17 May

Our country is definitely turning into some sort of

madhouse with lunatics in command, while people who have not yet lost their

reason huddle fearfully against the walls.

(From the newspaper Rech, cited in N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record

, Oxford 1955)

18 May

Memoir of Fedor Raskolnikov, naval cadet at Kronstadt

Hardly anywhere in Russia was the deputy of Prince Lvov and

Kerensky in such a pathetic situation as [Provisional Government commissar]

Pepelyayev was at Kronstadt. In actual fact he possessed no power: the fate of

Kronstadt was controlled by our valiant Soviet. [Author summoned to Lenin to

explain why the Soviet had taken control of Kronstadt.] We opened the door.

Comrade Lenin was sitting close to his desk and, his head bent low over the

paper, was hurriedly scribbling his next article for Pravda. When he had

finished writing he laid down his pen and directed at me a gloomy glance from

under his brows. ‘What have you been up to out there? How could you take such a

step without consulting the CC? This is a breach of party discipline. For such

things, we shall shoot people,’ said Vladimir Ilyich, giving me a dressing down.

[…] ‘Declaring Soviet power in Kronstadt alone, separately from all the rest of

Russia, is utopian, utterly absurd.’

(F.F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917

, New York 1982, first published 1925)

Diary entry of Joshua Butler Wright, Counselor of the American Embassy, Petrograd

The fever from which all Russia is suffering has spread to

our official servants now – and we have had two dvornik strikes since the revolution

… They demand impossible wages and simply refuse to leave the premises when

discharged on the ground that no one can be so treated in these days of

liberty! The black flag has again appeared in parades on the Nevsky this

afternoon in which workmen and extremists participated.

( Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J. Butler Wright

, London 2002)

19 May

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman

Yalta. All round and everywhere there is only anxiety.

Countess Betsy Schuvalov has just arrived from Kislovodsk, where she saw the

Grand Duchess Vladimir most days, and has brought me a piteous letter from her

in which she complains most bitterly of her lot. She has not been out of her

house for more than two months. As she has moved into a smaller house, she

lives entirely in one bed-sitting room. What can I do? Surely the best thing is

to do nothing; but how can she be expected to take this view, never in her life

having been denied anything?

(The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917

, New York 1919)

20 May

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

Today was the funeral of our old Stepanida Andreyevna

Skovorodina, who was taken on as wet-nurse to my brother Misha back in 1862 and

then served as our housemaid.

For the last few years she’s been living with Misha, but died in hospital. To

my shame, despite a call from Misha to remind me, it completely went out of my

mind and I only remembered late this evening. What’s terrible is not just

that I failed to pay my final respects to the deceased, but I inadvertently

showed a lack of consideration once again to the feelings of those closest to

me.

(Alexander Benois ,

Diary 1916-1918

, Moscow 2006)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

20 May 2017

History is written by the victors, said Churchill, Napoleon, Goring or Walter Benjamin (depending on your Google search outcome), but it’s equally true to say that it’s written by the elite, whether intellectual or social. Reading this week’s extracts, I can’t feel too much sympathy for Grand Duchess Vladimir (great name) and her down-sizing trials, while the thoughts of wet-nurse Stepanida Andreyevna would have been just as enlightening as those of her erstwhile charges. Perhaps more so. I suppose domestic staff, industrial workers and farm labourers had neither the education nor inclination (nor – above all – time) to sit at a desk and pontificate. More’s the pity. And it’s worth remembering this, that our sense of history as real, felt emotion – personalized history – comes very much from one sector of society, and it’s very easy to place all others into stereotyped categories: the oppressed peasantry, the militant factory workers, and so on.

The Socialist Worker online is running a weekly article about an aspect of the Revolution: https://socialistworker.co.uk/tag/view/628. While not necessarily righting this wrong, it does at least put the focus firmly back on to Trotsky’s definition of a history of a revolution, as ‘a history of a forcible entrance of the masses into the realm of rulership over their own destiny.’ For several months, this even seemed possible.