19-25 February 1917

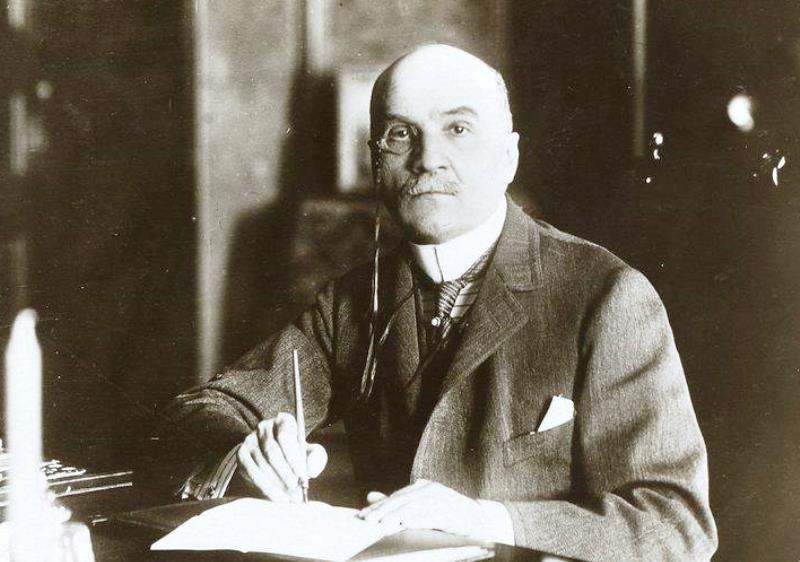

Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

Discontent among the masses in Russia is daily becoming more

marked. Disparaging statements concerning the Government are being voiced – at

first, they were surreptitious, and now, more bold and brazen, at meetings and

street corners. We feel sorry for the Imperial Family and especially for the

Tsar. He, it is said, wishes to please everybody and succeeds in pleasing

nobody. As time goes on, rumours of disorder become more persistent. Sabotage

has become the order of the day. Railroads are damaged; industrial plants

destroyed; large factories and mills burnt down; workshops and laboratories

looted. Now, rancour is turning towards the military chiefs. Why are the armies

at a standstill? Why are the soldiers allowed to rot in the snow-filled

trenches? Why continue the stalemate war? ‘Bring the men home!’ ‘Conclude

peace!’ ‘Finish this interminable war once and for all!’ Cries such as these

penetrate to the cold and hungry soldiers in their bleak earthworks, and begin

to echo among them.

(Florence Farmborough, Nurse at the Russian Front: A Diary

1914-18

, London 1974)

22 February

The Tsar, reassured by Protopopov that he had the situation

in hand, left for the front on February 22: he would return two weeks later as

Nicholas Romanov, a private citizen.

(Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution

, London 1995)

23 February

On Thursday, 23 February, the temperature in Petrograd rose

to a spring-like minus five degrees. People emerged from their winter

hibernation to enjoy the sun and join in the hunt for food. Nevsky Prospekt was

crowded with shoppers. The mild weather was set to continue until 3 March – by

which time the tsarist regime would have collapsed. Not for the first time in

Russian history the weather was to play a decisive role.

(Orlando Figes, A People's Tragedy

, London 1996)

Diary entry of Joshua Butler Wright, Counselor of the

American Embassy, Petrograd

The long threatening disturbances broke out quite suddenly

today in the shape of a general strike in the munitions factories – which

stopped for the first time since the war. The people paraded the Liteinyi, the

Nevsky Prospekt and other principal streets, many women being among them,

crying ‘Give us bread!’ The government has been prepared for a long time and

the Cossacks appeared as if by magic, driving back the people with the flat of

their sabers and with their wicked looking lances. They show great dexterity in

the handling of crowds and use their ponies cleverly. Rumor has it that a

police officer was killed by the mob. It is not a wicked demonstration but very

natural protests against present conditions. Dined at Korostovetz’s. Succeeded

in obtaining a Cossack guard for the Austrian embassy.

( Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J. Butler Wright

, London 2002)

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

It is to be

feared that revolutionary agitators and German agents are profiting by the

conditions. It is said that there is a certain amount of unrest in the suburbs.

I went out at about four o’clock to take Friquet for a walk, and went as far as

the Nevsky Prospekt. I met a small group of demonstrators who were, however,

quite quiet and surrounded by police. Everything is perfectly calm and the

passers-by watch them with amused sympathy. In Sadovaya Street the trams have

stopped … I don’t know whether it is because of other demonstrations, or simply

because of a power breakdown … That evening, a big dinner at the Embassy …

After dinner, Alexandre Benois confirms that there have been some incidents in

the outskirts. They say that at one place a tram was overturned.

(Louis de Robien, The Diary

of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918

, London 1969)

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

There was a grand dinner at Paléologue's this evening.

Something ominous is brewing!

On the Vyborg side there have been some widespread disturbances, the result of

bread shortages (the only surprise is that they haven’t happened sooner!) … We

wouldn’t have made it to Paléologue's because of the complete absence of cabs

had not the kind Gorchakovs sent a car for us … The embassy looked very

festive, with chandeliers ablaze and the dining table extended down the whole

length of the main dining-room upstairs … For some reason Paléologue had not

asked me to bring Prokofiev along again – seems that after the first time he

does not believe in the significance of this green-behind-the-ears young man.

[Louis] De Robien and I spent a good quarter of an hour in the recess of one of

the windows in the drawing room stealthily pulling back the curtains to follow what

was going on on Liteiny Bridge … we could see large crowds of people making

their way in a constant stream towards the city … The Gorchakovs took us home

as well. [Benois added the note: ‘We never imagined that this would be our last

visit, that the evening we had just enjoyed was the last gathering of

Petersburg society.’]

(Alexander Benois ,

Diary 1916-1918

, Moscow 2006)

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

I had

Trepov, Count Tolstoi, Director of the Hermitage, my Spanish colleague,

Villasinda, and a score of my regular guests to dinner this evening. The

occurrences in the streets were responsible for a shade of anxiety which marked

our faces and our conversation. I asked Trepov what steps the Government was

taking to bring food supplies to Petrograd, as unless they are taken the

situation will probably soon get worse. His replies were anything but

reassuring. When I returned to my other guests, I found all traces of anxiety

had vanished from their features and their talk. The main object of conversation

was an evening party which Princess Leon Radziwill is giving on Sunday: it wall

be a large and brilliant party, and everyone was hoping that there will be

music and dancing. Trepov and I stared at each other. The same words came to

our lips: ‘What a curious time to arrange a party!’ In one group, various

opinions were being passed on the dancers of the Marie Theatre and whether the

palm for excellence should be awarded to Pavlova, Kchechinskaia or Karsavina,

etc. In spite of the fact that revolution is in the air in his capital, the

Emperor, who has spent the last two months at Tsarskoie-Selo, left for General

Headquarters this evening.

(Maurice Paléologue,

An Ambassador's Memoirs 1914-1917

, London 1973)

Letter from Nicholas at General Headquarters to Alexandra

My own beloved Sunny,

Loving thanks for your precious letter – you left in my

compartment – I read it greedily before going to bed. It did me good, in my

solitude, after two months being together, if not to hear your sweet voice,

atleast [sic] to be comforted by those lines of tender love! …. It is so quiet

in this house, no rumbling about, no excited shouts! I imagine he [Aleksei] is

asleep in the bedroom! All his tiny things, photos & toys are kept in good

order in the bedroom & in the bowwindow [sic] room! Ne nado! On the other

hand, what a luck that he did not come here with me now only to fall ill &

lie in that small bedroom of our’s! God grant the measles may continue with no

complications & better all the children at once have it! … What you write

about being firm – the master – is perfectly true. I do not forget it – be sure

of that, but I need not bellow at the people right & left every moment. A

quiet sharp remark or answer is enough very often to put the one or the other

into his place. Now, Lovy-mine dear, it is late. Good-night, God bless our

slumber, sleep well without the animal warmth.

( The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and

the Empress Alexandra: April 1914-March 1917

, ed. Joseph T. Fuhrmann, London

1999)

24 February

Diary entry of James L. Houghteling, Jr, attaché at the American Embassy, Petrograd

Russia is a great place in which not to do shopping. The

salespeople simply don’t want to wait on you, don’t care whether you buy or

not. The foreigners leave them far behind in trade and the best shops are

manned with English, Belgians, Swedes and Baltickers. Formerly the Germans were

the great shop-keepers of Russia.

(James L. Houghteling, Jr, A Diary of the Russian Revolution

, New York 1918)

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman

Drove to the French Hospital. Just after crossing the

Nicolai Bridge I met a demonstration singing the ‘Marseillaise’. They were

prevented from crossing the bridge, so turned back and went up the 8th Linea

Street. I got out of my sledge, and telling the man to wait I joined them and

went with them as far as the Bolschoie Prospekt. They were accompanied by

Cossacks. They were not harassed at all, and the Cossacks chaffed them and

talked to the children: all were on the best of terms. I wanted to see how they

behaved and how they were treated. Tout était à

l’aimable. When I left them I walked back to my sledge and went on to the

hospital.

(The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917

,

New York 1919)

25 February

Letter from Alexandra at Tsarskoe Selo to Nicholas

My own priceless, beloved treasure

8° & gently snowing – so far I sleep very well, but miss you

my Love more than words can say. – The rows [disorders] in town and strikes are

more than provoking … Its a hooligan movement, young boys & girls running

about & screaming that they have no bread, only to excite - & then the

workmen preventing others fr. work – if it were very cold they wld. probably

stay in doors. But this will all pass & quieten down – if the Duma wld.

only behave itself – one does not print the worst speeches but I find that

antidynastic ones ought to be at once very severely punished as its time of

war, yet more so.

( The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and

the Empress Alexandra: April 1914-March 1917

, ed. Joseph T. Fuhrmann, London

1999)

Memoir of A.P. Balk, Governor of Petrograd

February 25 was a total defeat for us. Not only were the

leaders of the revolutionary actions convinced that the troops were acting

without spirit, even unwillingly, but the crowd also sensed the weakness of the

authorities and became emboldened. The decision of the military authorities to

impose control by force, in exceptional circumstances to use arms, not only

poured oil on the fire but shook up the troops and allowed them to think that

the authorities … feared ‘the people’.

(Ronald Kowalski, The Russian Revolution 1917-1921

,

London & New York 1997)

Extract from a history of the revolution

Whatever chance there was of containing the incipient

rebellion was destroyed with the arrival in the evening of February 25 of a

telegram from Nicholas to the city’s military commander demanding that he

restore order by force. Nicholas, who continued to receive soothing reports

from Protopopov, had no idea how charged the situation in the capital had

become.

(Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution

, London 1995)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov

During the first revolutionary upsurge, February 24th-25th,

my attention was taken up not by the programmatic aspect … of this political

problem, but its other, tactical side. Power must go to the bourgeoisie. But

was there any chance that they would take it? What was the position of the

propertied elements on this question? Could they and would they march in step

with the popular movement? Would they, after calculating all the difficulties

of their position, especially in foreign policy, accept power from the hands of

the revolution? Or would they prefer to dissociate themselves from the

revolution which had already begun and destroy the movement in alliance with

the Tsarist faction? Or would they, finally, decide to destroy the movement by

their ‘neutrality’ – by abandoning it to its own devices and to mass impulses

that would lead to anarchy?

(The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record by N.N. Sukhanov,

Oxford 1955)

Alexander Shliapnikov, leading Bolshevik and later first Soviet Commissar of Labour

What revolution? Give the workers a pound of bread and the movement will fizzle.

(cited in Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution

, London 1995)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

25 February 2017

Hisham Matar, the British-Libyan writer, has written a powerful book, The Return

, about his family's involvement with the opposition struggle in Libya from before and since independence. 'Revolutions have their momentum', he writes, 'and once you join the current it is very difficult to escape the rapids. Revolutions are not solid gates through which nations pass but a force comparable to a storm that sweeps all before it.' A hundred years ago, Russia was about to experience the first storm, one that swept away centuries of tsarist rule and left Russia with an opportunity - a genuine democratic moment - that for a few short months it tried to grasp. But the momentum Matar refers to seems inescapable, the consequences can go far beyond those anticipated. And as with his desperate attempts to find out what happened to his father, the personal cost - the tragedy - of revolution is immeasurable.