19-25 March 1917

Funeral of the 'martyrs of the Revolution' on the Field of Mars (Champ de Mars), Thursday 23 March

Memoirs of

Evgeny Drashusov, naval officer

A new life began. Whilst through inertia the old forms were

retained, its content was fundamentally transformed… Going to work became little short of a

punishment. Normal business ceased and as with everything else it turned into

something monstrous, laborious and at the same time childishly naïve. From the

start we were forced to play at equality and solidarity with our inferiors. The

pen-pushers majestically inveigled themselves into the running of things,

pulling а revolver and some kind of all-powerful revolutionary ‘mandate’ from

their pocket at the slightest hint of dispute. We unfortunates, not knowing

who to rely on and sensing the same situation at the top, where the role of our pen-pushers was played by the Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies, dragged

ourselves around and – alas – instead of any active response just dreamed of

being magically spirited away from it all … A couple of weeks after

the ‘liberation’, I received a telegram from my father in Yurakov, our estate

in Ryazan province, where my parents and two sisters were living at the time.

The telegram confirmed what I had feared. Our peasants … had quickly grasped

the way things were going and had begun to stir and make demands which the

household didn’t want to respond to without me. I quickly took time off and

with a heavy heart and foreboding … went back home. … I found everyone alarmed

and dejected. After hearing the first news of what had happened, and particularly

after the Tsar’s abdication, my father had stopped reading the papers and with

the profound suffering of an old man of conviction had silently begun to expect

the worst.

( Russia in

1917 in first-person testimony

, Moscow 2015)

19 March

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

General Kornilov, the new Military Governor of Petrograd, is

endeavouring gradually to resume control of the troops of the garrison. The

task is all the more arduous because most of the officers have been killed,

degraded or forced to fly … A consignment of newspapers, the latest of which is

eleven days old, has reached me from Paris and strengthens me in a view I took

on reading the daily

résumés

transmitted by telegraph. The French public is

enthusiastic for the Russian revolution! Once again our press will have been

found wanting in moderation and judgement.

(Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs 1914-1917

,

London 1973)

Diary entry of James L. Houghteling, Jr, attaché at the American Embassy, Petrograd

We have heard that at Kronstadt the sailors revolted with

much bloodshed, killing 170 officers, including a very efficient and popular

admiral who had been put in command at the request of the British. The sailors

seem to be responsible for the few excesses of the revolution.

(James L. Houghteling, Jr, A Diary of the Russian Revolution

, New York 1918)

Memoir of Fedor Raskolnikov, naval cadet at Kronstadt

Soon afterward there hastened into the room

[at Gorky’s

flat] where I was awaiting the end of this rather boring meeting the well-known

writer I. Bunin, who is now on the run. When he learnt that I had come from

Kronstadt, Bunin bombarded me with a whole heap of philistine questions: ‘Is it

true that anarchy reigns in Kronstadt? Is it true that unimaginable excesses

are going on there? Is it true that the sailors are killing any officer they

come upon in the streets of Kronstadt?’ In a tone that permitted no objection I

rebutted all these bourgeois calumnies. Bunin, sitting with his legs crossed on

the ottoman, listened with great interest to my calm explanations and fixed his

sharp eyes upon me. My officer’s uniform evidently gave him confidence, as he

offered no objections to what I said.

(F.F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917

,

New York 1982, first published 1925)

21 March

Memoir of Princess Paley

The life of the august prisoners was monotonous, mournful,

devoid of all joy. The restrictions were rigorous. The Provisional Government

granted them credits, characterised by the utmost parsimony. All their letters

were opened, the use of the telephone was denied them. Boorish, and frequently

drunken, sentries were posted everywhere. The sole distraction of the Emperor

was to break up the ice on a little canal which runs along the barrier of the

Imperial Park.

(Princess Paley, Memories of Russia, 1916-1919

, London 1924)

Diary entry of Nicholas II

After lunch, I went out into the park with Alexei and spent

the time breaking the ice by our summer landing pier; a crowd of loiterers

again stood by the railings and stared at us from start to finish.

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion

, London 1996)

22 March

Letter from Sofia Yudina in Petrograd to her friend Nina Agafonnikova

in Vyatka

My dear Ninochka!

… Do you read the papers, maybe it’s not interesting for you

or they don’t allow it? Here we spend a lot of time poring over the papers. I

get up late (what a bore!):

earlier than 10 I can’t even think of getting up! I get up, drink some coffee

and read the papers, then I play [the piano], and get on with other things –

somehow everything moves at such a slow pace here… I agree with this point of

the social-democratic programme – to limit and take over landed estates – but

it really worries Papa and Mama: they’ve put so much into Polyana, created it

through their own hard work and have looked upon it as a little refuge for when

they are old. Now this probably won’t happen… Moreover, lessons have almost

stopped, all these Romanovs are leaving, the price of everything is going up –

and Papa is very worried, he’s getting tired … Tomorrow is the funeral of those

who lost their lives on the Field of Mars: sounds like it will be quite a

ceremony, judging by the programme for the procession. We will probably stay at

home … we won’t see anything anyway, better to read about it in the papers.

(Viktor

Berdinskikh, Letters from Petrograd: 1916-1919

, St Petersburg 2016)

23 March

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

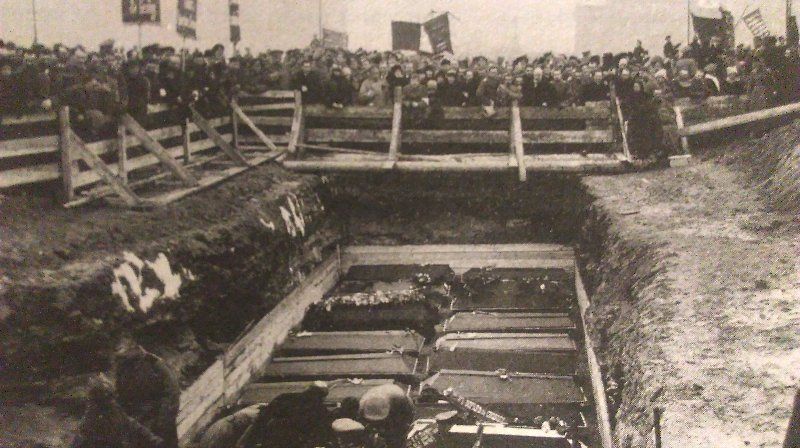

Today there has been a great ceremony on the Champ-de-Mars,

where the victims of the revolutionary rising, the ‘nation’s heroes’ and

‘martyrs to liberty’, have been given a state burial … Since early morning,

huge and interminable processions, headed by military bands and carrying black

banners, threaded their way through the streets of the city to collect from the

hospitals the two hundred and ten coffins destined for revolutionary

apotheosis.

(Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs 1914-1917

,

London 1973)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov

It would be an understatement to say that the funeral went

off brilliantly. It was a magnificent and moving triumphal procession of the

revolution and of the masses who made it. As for its size, it surpassed

anything ever seen. Buchanan, the British Ambassador, watched it from his

Embassy, whose windows looked on to the Champ de Mars and the Neva Embankment,

and stated categorically that Europe had never seen anything like it. But the

size of the demonstration was not the most important thing on that remarkable

day of March 23rd. This time the entire press without exception had to admire

the standard of citizenship displayed by the masses of the people in this

majestic review. All fears proved groundless. In spite of the hitherto

unheard-of number of demonstrators, which undoubtedly reached a million, the

order was not only irreproachable but – in the words of the same Buchanan –

‘unbelievable’ … This was no funeral but a great, unclouded triumph of the

people, which long remained a grateful memory with all those who took part in

it. I did not take part in it myself, any more than in most such

demonstrations.

(The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record by N.N. Sukhanov,

Oxford 1955)

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman

The burial procession of the victims of the Revolution in

the Champ de Mars began to pass the end of Michail Street along the Nevski at

8.40. During the next three hours I saw only four coffins go by, and there were

in all only twelve coffins in that procession which passed up the Nevski.

(The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917

, New York 1919)

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

On the emblems there are inscriptions: ‘Eight-hour days’ –

‘Social Republic’ – ‘Votes for Women’ and, above all, ‘Zemlya i volya – land and liberty – which apparently was the battle

cry of the peasant who revolted against Catherine the Great under the

leadership of Pougachev … In Russia nothing changes.

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918

, London 1969)

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

The most chilling

moment was when … there appeared, behind the black banners, the first two

coffins, covered in bright-red cloth.

This spoke particularly clearly of the new spirit of the time and the break

with deeply held traditions (I never expected my compatriots to break so

audaciously with the sacred rituals of death); it signified something malignant

and defiant.

(Alexander Benois ,

Diary 1916-1918

, Moscow 2006)

Memoir of Pierre Gilliard, tutor to the Tsar’s children

Whenever we go out, soldiers, with fixed

bayonets and under the command of an officer, surround us and keep pace with

us. We look like convicts with their warders. The instructions are changed

daily, or perhaps the officers interpret them each in his own way! This

afternoon, when we were going back to the palace after our walk, the sentry on

duty at the gate stopped the Tsar, saying: ‘You cannot pass, sir.’ The officer

with us intervened. Alexei blushed hotly to see the soldier stop his father.

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion

, London 1996)

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman

Each time the guard is changed there is a regular scrimmage

amongst the soldiers as to who should be on guard in the palace and who should

be outside in the park. Everyone desires to be near the Emperor, such is the

love of the Russian for his Little Father.

(The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917

, New York 1919)

25 March

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

The declaration of war by the United States has had no

effect whatsoever on the Russian people … In spite of their lofty principles,

the United States are only coming into the war to get their money back …

Besides, they are on the other side of the Atlantic. When one thinks about it

all, one wonders what use their alliance can be to us at the moment, except by

way of moral support!

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918

, London 1969)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

25 March 2017

A Hermitage translation for its forthcoming Anselm Kiefer exhibition has wiped out this week, hence this late posting. But the different takes on the event of the week - the funeral (on 23 March) of those who lost their lives in the immediate aftermath of the revolution - is another reminder of how history depends almost entirely on who's writing it. Managed at last to get to the Royal Academy Revolution

exhibition which is every bit as good as everyone says. In his introduction to the catalogue, co-curator John Milner highlights the significance of artists in promoting the new world order, not just the well-known names of the avant-garde but more conventional academic painters like Isaak Brodsky who painted famous portraits of Lenin and Stalin: 'The Bolshevik government needed recognisable images of its leaders and heroes to consolidate the foundation myths on which the Soviet state was constructed.' Still, pretty hard, in my view, to beat Alexander Deineka and his extraordinary paintings.

It was while we were in the Royal Academy that the attack on Westminster Bridge took place. Random loss of life today, no less than a hundred years ago; freedoms that need defending, no less than a hundred years ago.