3-9 September 1917

Lotarevo estate, Tambov province (former home of the Vyazemsky family)

Across the empire, the Mensheviks were splintering. Some

went to the right, as in Baku; at the other extreme, the Mensheviks in Tiflis,

Georgia, took a hard-left position for a united socialist government that would

include the Bolsheviks … And whether or not dissent took socialist forms, the

national aspirations of Russia’s minorities were amplifying … From the 8th to

the 15th, the Ukrainian Rada provocatively convened a Congress of the

Nationalities, bringing together Ukrainians, Jews, Poles, Lithuanians, Tatars,

Turks, Bessarabian Romanians, Latvians, Georgians, Estonians, Kazakhs, Cossacks

and representatives of various radical parties … dynamics towards independence

in some form were at least implicit.

(China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution

, London 2017)

3 September

Report in The Times

Petrograd – The Government has issued the following official

manifesto declaring the establishment of a Republic:- The rebellion of General

Korniloff has been suppressed, but the trouble which the Army has brought upon

the country is great. Once again mortal danger threatens the liberty of the

Fatherland. Deeming it necessary to define the political status of the country,

and taking into consideration the sympathy, unanimity, and enthusiasm for the

Republican idea that were so clearly evident at the Moscow Conference, the

Provisional Government hereby declares that the political regime of Russia is

Republican, and proclaims Russia a Republican State.

('Government Manifesto', The Times

, 3 (16) September 1917)

4 September

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman

A Prince Viazemski has been murdered by his peasants – his

eyes first put out and his sufferings prolonged for several hours. His young

wife was in the house and had to witness it all.

(The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917

, New York 1919)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov

Trotsky had been released from prison on September 4th, just

as suddenly and causelessly as he had been arrested on July 23rd. Now he became

chairman of the Petersburg Soviet; there was a hurricane of applause when he

appeared!

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record

, Oxford 1955)

5 September

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Today the government proclaimed the Republic, in order to

satisfy public opinion … and seized the opportunity to double the price of

bread. A theoretical price, in fact, because there is none to be had.

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918

, London 1969)

6 September

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Bad news from Finland. The massacres of officers continue.

At Viborg half a dozen of them were thrown off the bridge into the river and

finished off with gun-shots. At Helsingfors the sailors murdered several navy

officers with blows from a hammer. Murders like these are said to be happening

almost everywhere, but they have been kept from the public.

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918

, London 1969)

7 September

Report in The Times

The committee system has been most disastrous in its effect

upon industries. Workmen are too busy with politics to attend to their duties.

Locomotives and rolling stock are not repaired. The complete paralysis of

transport, the stoppage of all industries, owing to the shortage of fuel and

raw materials, is a question of months or weeks, perhaps days. The output of

munitions has declined by 80 per cent.

(‘Russia Today: The Committee System’, The Times

, By our

Petrograd Correspondent)

8 September

Diary of Nicholas II

We went for the first time to the church of the Annunciation, where our priest has served for a long time. But the pleasure was spoilt for me by the idiotic conditions in which we had to walk there. Sentries were posted all along the path of the town park, where there was no one, while there was a huge crowd at the church! I was deeply upset.

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion

, London 1996)

Diary entry of Joshua Butler Wright, Counselor of the American Embassy, Petrograd

Alekseev has resigned - as rumored last night - on the ground that the government would not agree to his recommendations relative to the restoration of strict discipline in the army! The members of four cavalry regiments have announced that all their officers who are of noble lineage are to be deprived of their commands by order of their men ... I have determined to send Mrs Wright and Butler tomorrow night to spend a few weeks with the Summers. The situation here is not so reassuring as to incline me to leave them here.

( Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J. Butler Wright

, London 2002)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

9 September 2017

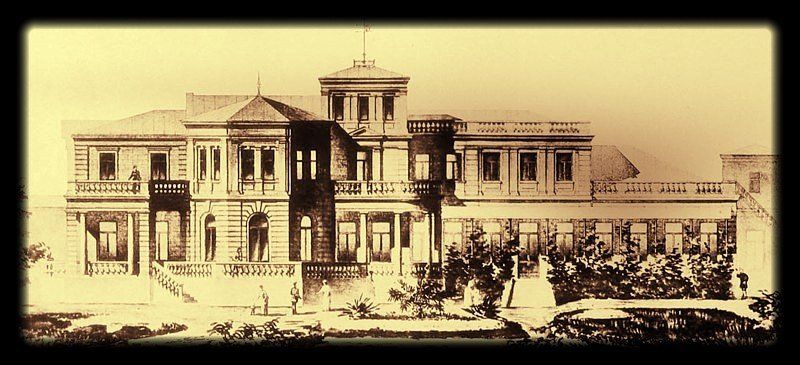

The murder of Prince Vyazemsky, mentioned with characteristic flourish (and artistic licence) by our Anonymous Englishman, had happened a couple of weeks earlier and provides an interesting example of differing historical interpretations. In some accounts Vyazemsky is described as a gentle and generous man who built schools, roads and bridges, kept records of seasonal changes on

his Lotarevo estate, planted new species of trees and spent most of his time poring over his numerous books on botany and ornithology. The

account of his death in the local Tambov paper suggests that it was almost a chance occurrence that led to his brutal murder – that prosaic business of being in the wrong place at the wrong time: ‘The mob who had arrested

Prince Vyazemsky made it a condition of his release that he should be sent

immediately to the front. The prince agreed to this and was sent under convoy

to Gryazi station for further onward despatch to join the Army. At this moment

a train with a squadron of soldiers came into the station. Hearing of the incident with Vyazemsky, they

immediately started taunting him and after cruel torture the prince was killed

by the enraged mob. It later became known that one of the best cultivated estates

in Russia – Prince Vyazemsky’s Lotarevo estate – was completely

destroyed.’ In his book A People's Tragedy

, Orlando Figes gives a rather different version of events: 'This violent wave of destruction seems to have started with the murder of Prince Boris Vyazemsky, the owner of several thousand hectares in the Usman region of Tambov. The local peasants had been demanding since the spring that Vyazemsky lower his rents and return the hundred hectares of prime pasture he had taken from them as a punishment for their part in the revolution of 1905. But on both counts Vyazemsky had refused. On 24 August some 5,000 peasants from the neighbouring villages occupied the estate. Fortified by vodka from the prince's cellars, and armed with pitchforks and rifles, they repulsed a Cossack detachment, arrested Vyazemsky and organised a kangaroo court which decided to despatch him to the Front, "so that he can learn to fight as the peasants have done". But there were also cries of "Let's kill the Prince! We are sick of him!", and he was murdered by the drunken mob before he even reached the nearby railway station.' So gentle botanist or sadistic landowner, murdered on his estate by his peasants or at the station by unruly soldiers - the window into the past is nothing if not opaque.