13-19 August 1917

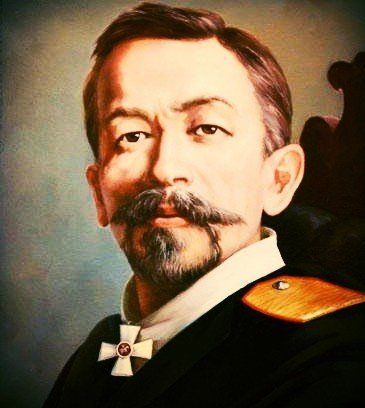

A wiry little little man with strong Tartar features. He wore a general's full-dress uniform with a sword and red-striped trousers. His speech was begun in a blunt soldierly manner by a declaration that he had nothing to do with politics. He had come there, he said, to tell the truth about the condition of the Russian army. Discipline had simply ceased to exist. The army was becoming nothing more than a rabble. Soldiers stole the property, not only of the State, but also of private citizens, and scoured the country plundering and terrorizing. The Russian army was becoming a greater danger to the peaceful population of the western provinces than any invading German army could be.

British journalist Morgan Philips Price, reporting on Kornilov in August 1917

13

August

Message from President Wilson to the National Conference in Moscow

I take the liberty to send to the members of the great council now meeting

in Moscow the cordial greetings of their friends, the people of the United

States, to express their confidence in the ultimate triumph of ideals of

democracy and self-government against all enemies within and without, and to

give their renewed assurance of every material and moral assistance they can

extend to the Government of Russia in the promotion of the common cause in

which the two nations are unselfishly united.

( Russian-American Relations: March 1917-March 1920

, New York 1920)

14

August

Diary entry of Joshua Butler Wright, Counselor of the American Embassy,

Petrograd

No news of Moscow conference today, no papers being published, and telephone

connection with Moscow very poor. We have extended one hundred million dollars

more to Russia with the distinct proviso, however … that it is to be expended

for specific purposes ‘on the condition that Russia continues the struggle

against the common enemy.’

( Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J.

Butler Wright

, London 2002)

When [Kornilov] arrived in Moscow on August 14, over Kerensky’s objections,

to attend a State Conference, he was wildly cheered. For Kerensky, who regarded

Kornilov’s reception as a personal affront, this incident marked a watershed.

According to his subsequent testimony, ‘after the Moscow conference, it was

clear to me that the next attempt at a blow would come from the right and not

from the left’.

(Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution

,

London 1995)

Diary of Zinaida Gippius

Kerensky is a railway car that has come off the tracks. He wobbles and sways

painfully and without the slightest conviction. He is a man near the end and it

looks like his end will be without honour.’

(Orlando Figes, A People's Tragedy

, London 1996)

Valia Dolgorukov to his brother Pavel from Tobolsk

My dear Pavel,

We arrived in Tobolsk at 6 in the evening. In order to see the house and

find out what had been prepared, Makarov and I decided to go into town before

the others and do a reconnaissance. The picture was depressing in general, and

in complete contrast to Ivan’s description … a dirty, boarded up, smelly house

consisting of 13 rooms, with some furniture, and terrible bathrooms and toilets

… This is the seventh day when we are cleaning, painting and getting the houses

in order while we and the family are still on the steamboat Russia. The cabins

are very small and the facilities, for women at least, miserable. Alexei and

Maria have caught cold. His arm is hurting a lot and he often cries at night. Gilliard

has been lying in his cabin for the last eight days, he has some sort of boils

on his arm and legs. And a slight fever. It is easier to get provisions here

and significantly cheaper. Milk, eggs, butter and fish are plentiful. The

family is bearing everything with great sang-froid and courage.

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion

, London 1996)

18 August

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to the Imperial Court

I could not … conceal from [Kerensky] how painful it was to me to watch what

was going on in Petrograd. While British soldiers were shedding their blood for

Russia, Russian soldiers were loafing in the streets, fishing in the river and

riding on the trams, and German agents were everywhere. He could not deny this,

but said that measures would be taken promptly to remedy these abuses.

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia

, London 1923)

19 August

All rumours of incipient coups notwithstanding, after the Moscow conference,

Kerensky was willing to accept the crushing curbs on political rights that

Kornilov demanded, hoping they might stem the tide of anarchy … Kornilov

pressed his advantage. On 19 August, he telegraphed Kerensky to ‘insistently

assert the necessity’ of giving him command of the Petrograd Military District,

the city and areas surrounding. At this, though, Kerensky still drew the line.

(China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution

, London

2017)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

19 August 2017

I keep claiming to be through with historical parallels, but sometimes they're hard to avoid. August is a strange month when politics takes time off and journalists hunt around for things to write about. In Russia August seems to be a month for abortive coups: Kornilov's in 1917; the putschists in 1991. In both instances the coup's failure in the short term heralded the government's demise a little further down the line, and helped bring to power regimes antipathetic to the coup's aims. In 1917 it was the Bolsheviks; in 1991, it was Boris Yeltsin, President of the Russian Federation, whose resistance to the coup enhanced his popular support. For those who may have forgotten the chain of events in 1991, here's a potted resume:

'The coup of August 1991 was timed to prevent the signing of the new Union Treaty which would have fundamentally recast the relationship between the centre and the republics in favour of the latter, and was scheduled for 20 August. On 18 August, a group of five military and state officials arrived at Gorbachev’s presidential holiday home on the Crimean coast to attempt to persuade him to endorse a declaration of a state of emergency. Gorbachev’s angry refusal to do so was the first indication that the coup plotters had miscalculated. While Gorbachev was held virtual prisoner, the State Committee ordered tanks and other military vehicles into the streets of the capital and announced on television that they had to take action because Gorbachev was ill and incapacitated. Some of the republics’ leaders went along with the coup; others adopted a wait-and-see approach. A few declared the coup unconstitutional. Among them was Yeltsin who made his way to the White House, the Russian parliament building, and, with CNN’s cameras rolling, mounted a disabled tank to rally supporters of democracy. The soldiers and elite KGB units ordered into the streets by the State Committee refused to fire on or disperse the demonstrators. By 21 August the leaders of the coup had given up. An exhausted Gorbachev returned to Moscow to find it totally transformed. When he visited the Russian parliament, Yeltsin's stronghold, he was humiliated by Yeltsin and taunted by the deputies. Reluctantly, he agreed to Yeltsin's dissolution of the Communist Party which was held responsible for the coup and resigned as the party’s General Secretary. Yeltsin thereupon proceeded to abolish or take over the institutions of the now moribund Soviet Union' (Lewis Siegelbaum). I remember August 1991 well since I was supposed to be flying to Moscow the day it all started but my flight was cancelled. Or maybe I chickened out. History doesn't relate...