30 April - 6 May 1917

- By Mark Sutcliffe

- •

- 06 May, 2017

- •

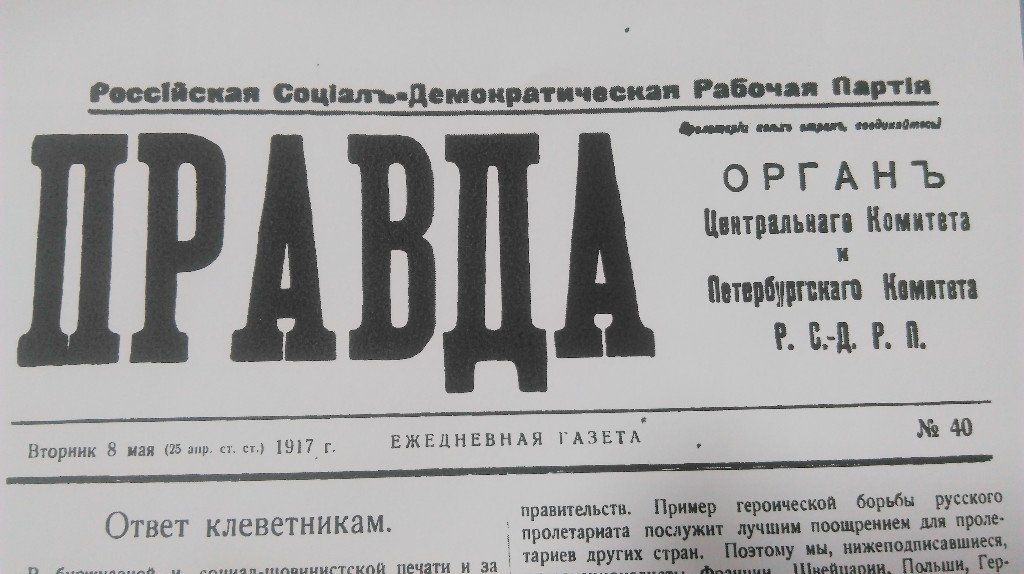

The Bolsheviks influenced minds mainly by means of the

printed word. By June, Pravda had a

run of 85,000 copies. They also put out provincial papers, papers addressed to

special groups (e.g. female workers and ethnic minorities), and a multitude of

pamphlets. They paid particular attention to the men in uniform … In the spring

of 1917 they distributed to the troops about 100,000 papers a day, which, given

that Russia had 12 million men under arms, was enough to supply one Bolshevik

daily per company … These publications spread Lenin’s message, but in a veiled

form … Such organisational and publishing activities required a great deal of

money. Much, if not most, of it came from Germany.

(Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, London 1995)

30 April

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

To summarise my acquaintance [with French ambassador

Paléologue] I will say that I judge him less than others … On a purely personal

basis I regret that I’m losing a pleasant, lively and amusing companion …

Moreover, he has a very low opinion of our government’s mindset, including

Kerensky. He has the impression that the Provisional Government is just a

continuation of hapless

Nicholas II. And therefore it’s the undoubted downfall of the first act of the

Russian Revolution.

(Alexander Benois,Diary 1916-1918, Moscow 2006)

1 May

Article in The Times

Discussion of developments in Russia is still confined

rigidly in Germany to the Socialist Press. For weeks past the non-Socialist

organs, although they cannot conceal their excitement about the prospects of

the Stockholm plot, have published no serious comment on the Russian situation.

But they were moved to paroxysms of joy by the false report of the departure of

the British Ambassador from Petrograd. The Cologne

Gazette learned from Copenhagen that Sir George Buchanan left the British

Embassy secretly, ‘by a back-door’. The Munchner

Neuste Nachrichten reported from Berlin that the Ambassador had ‘made

himself impossible’ in Petrograd, and would not return. The Berliner Tageblatt, after expressing

some slight doubt as to the accuracy of the news, said: ‘The sudden departure

of the Ambassador is very natural. It is explained by his recognition that his

part is finished, and that there remains nothing for him to do on Russian soil,

since the policy pursued by him and, under his influence, by the Provisional

Government, has been shattered ... The English statesmen, unless they want to experience fresh

disasters, will have to send to the Neva a different Ambassador with quite

different instructions.’

('The Plot against Russia', The Times)

A great impression has been produced here by General Brusiloff’s latest speech, which points out certain serious shortcomings in the Army and deplores the agitation for the conclusion of a premature peace, the relaxation of discipline, the number of deserters, and the tendency to fraternize with the enemy that has manifested itself since Easter. He stated that the enemy tempted the troops by offers of vodka, and endeavoured to deceive them by proclamations. He mentioned an instance in which the Russian artillery had prepared to fire on Germans advancing with vodka and white flags. He also dwelt on the numbers of deserters, who exercised a baneful influence in the rear, along the railways, and in the villages. He declared that lack of discipline must entail the ruin of Russia.

('Vodka and White Flags', The Times, from our own correspondent in the Balkan peninsula)

4 May

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Russia has slipped further down the dangerous slope.

Kerensky becomes Minister for War in the place of Guchkov. Milyukov is expected

to be replaced by Tereschenko. Nobody knows yet whether the other Kadets will

remain. The situation is serious: and the fact that Sazonov did not leave for

London clearly shows the change in Russian policy as it concerns the conduct of

the war. The worst is to be feared from Russia, who staged the revolution in

order to have peace, and who wants peace at any price … Several people coming

from Moscow and Kiev tell me that these two towns are as contaminated as

Petrograd. And yet, up to now there have been no serious disturbances in the

big centres. It is, rather, a slow disintegration. It is not the same in the

country districts. The soldiers charged with keeping order in the surroundings

of Orel have joined forces with the peasants. They have pillaged the stocks of

alcohol and have set fire to all the estates. The newspapers say that the

horizon is a red circle every night in this district.

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918, London 1969)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov

By 2 o’clock in the morning of May 5th everything was ready. The portfolios have been quickly assigned, and all the doubtful points settled in this way: Kerensky got the War Ministry and the Admiralty, Pereverzev the Ministry of Justice; Peshekhonov Supply, Skobelev Labour, Tsereteli Posts and Telegraphs. The Coalition had been created. The formal union of the Soviet petty-bourgeois majority with the big bourgeoisie had been ratified in a written constitution … Now only the last act remained, the final chord, the apotheosis.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record, Oxford 1955)

Letter to the independent socialist newspaper Novaia zhizn

To All Russian Women and Mothers

We, a group of Russian women and mothers, are joining the

protest of the working people against the war. We are also extending our hand

to women and mothers the world over. We are deeply convinced that our extended

hand will meet the extended hands of mothers the world over. No annexations or

indemnities can compensate a mother for a murdered son. Enough blood. Enough of

this horrible bloodshed, which is utterly pointless for working people. Enough

of sacrificing our sons to the capitalists’ inflamed greed. We don’t need any

annexations or indemnities. Instead, let us safeguard our sons for the good of all

the working people the world over. Let them apply all their efforts not to a

fratricidal war but to the cause of peace and the brotherhood of all peoples.

And let us, Russian women and mothers, be proud knowing that we were the first

to extend our brotherly hand to all the mothers the world over.

Smolensk Initiative Group of Women and Mothers

(Mark D. Steinberg, Voices of Revolution, 1917, New Haven and London 2001)

6 May

Declaration by the Second Provisional Government, published in Izvestiia

Reorganised and strengthened by the entrance of new representatives of the Revolutionary Democracy, the Provisional Government declares that it will resolutely and whole-heartedly put into practice the ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity - under whose banner the great Russian Revolution has come into being.

(Russian-American Relations March 1917-March 1920, New York 1920)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

6 May 2017

This week's posting draws on several newspapers - German, Russian and British. In today's Guardian the novelist China Miéville muses on the relevance of the revolution for the world today. In fact he asks a very similar question to the one I put to Russian friends in St Petersburg a few weeks ago: how the government will mark the anniversary in October. 'Would it remember the centenary with celebration or anathema? "They will say there was a struggle," I was told, "and that eventually, Russia won."' He quotes the dissident Bolshevik Victor Serge, writing in 1937: 'It is often said that "the germ of all Stalinism was in Bolshevism at its beginning. Well, I have no objection. Only, Bolshevism also contained many other germs, a mass of other germs, and those who lived through the enthusiasm of the first years of the first victorious socialist revolution ought not to forget it. To judge the living man by the death germs which the autopsy reveals in the corpse - and which he may have carried in him since birth - is that very sensible?' Miéville makes an interesting point about the revolution turning in on itself: 'Without hope there's no drive to overturn an ugly world. Without pessimism, a frank evaluation of the difficulties, necessities can all too easily be recast as virtues. Thus after Lenin's death the party's adoption of Stalin's 1924 theory of "socialism in one country". This overturned a long commitment to internationalism, the certainty that the Russian revolution could not survive in isolation. The failure of the European revolutions provoked this - it was a shift born of despair. But announcing, ultimately celebrating, an autarchic socialism was a catastrophe. A hard-headed pessimism would have been less damaging than this bad hope.'

8 October

Letter from Lenin to the Bolshevik Comrades attending the Regional Congress of

the Soviets of the Northern Region

Comrades, Our revolution is passing through a highly critical period …

A gigantic task is being imposed upon the responsible leaders of our Party,

failure to perform which will involve the danger of a total collapse of the

internationalist proletarian movement. The situation is such that verily,

procrastination is like unto death … In the vicinity of Petrograd and in

Petrograd itself — that is where the insurrection can, and must, be decided on

and effected … The fleet, Kronstadt, Viborg, Reval, can and must advance

on Petrograd; they must smash the Kornilov regiments, rouse both the capitals,

start a mass agitation for a government which will immediately give the land to

the peasants and immediately make proposals for peace, and must overthrow

Kerensky’s government and establish such a government. Verily, procrastination

is like unto death.

(V.I. Lenin and Joseph Stalin, The Russian Revolution: Writings and Speeches

from the February Revolution to the October Revolution, 1917, London 1938)

9 October

Report in The Times

The Maximalist [Bolshevik], M. Trotsky, President of the Petrograd Soviet,

made a violent attack on the Government, describing it as irresponsible and

assailing its bourgeois elements, ‘who,’ he continued, ‘by their attitude are

causing insurrection among the peasants, increasing disorganisation and trying

to render the Constituent Assembly abortive.’ ‘The Maximalists,’ he declared,

‘cannot work with the Government or with the Preliminary Parliament, which I am

leaving in order to say to the workmen, soldiers, and peasants that Petrograd,

the Revolution, and the people are in danger.’ The Maximalists then left the

Chamber, shouting, ‘Long live a democratic and honourable peace! Long live the

Constituent Assembly!’

(‘Opening of Preliminary Parliament’, The Times)

10 October

As Sukhanov left his home for the Soviet on the morning of the 10th, his

wife Galina Flakserman eyed nasty skies and made him promise not to try to

return that night, but to stay at his office … Unlike her diarist husband,

who was previously an independent and had recently joined the Menshevik left,

Galina Flakserman was a long-time Bolshevik activist, on the staff of Izvestia.

Unbeknownst to him, she had quietly informed her comrades that comings and

goings at her roomy, many-entranced apartment would be unlikely to draw

attention. Thus, with her husband out of the way, the Bolshevik CC came

visiting. At least twelve of the twenty-one-committee were there … There

entered a clean-shaven, bespectacled, grey-haired man, ‘every bit like a

Lutheran minister’, Alexandra Kollontai remembered. The CC stared at the

newcomer. Absent-mindedly, he doffed his wig like a hat, to reveal a familiar

bald pate. Lenin had arrived.

(China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution, London 2017)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai

Sukhanov

Oh, the novel jokes of the merry muse of History! This supreme and decisive

session took place in my own home … without my knowledge … For such a

cardinal session not only did people come from Moscow, but the Lord of Hosts

himself, with his henchman, crept out of the underground. Lenin appeared in a

wig, but without his beard. Zinoviev appeared with a beard, but without his

shock of hair. The meeting went on for about ten hours, until about 3 o’clock

in the morning … However, I don’t actually know much about the exact

course of this meeting, or even about its outcome. It’s clear that the question

of an uprising was put … It was decided to begin the uprising as quickly

as possible, depending on circumstances but not on the Congress.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record, Oxford 1955)

11 October

British Consul Arthur Woodhouse in a letter home

Things are coming to a pretty pass here. I confess I should like to be out

of it, but this is not the time to show the white feather. I could not ask for

leave now, no matter how imminent the danger. There are over 1,000 Britishers

here still, and I and my staff may be of use and assistance to them in an

emergency.

(Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917, London 2017)

Memoir of Fedor Raskolnikov, naval

cadet at Kronstadt

The proximity of a proletarian rising in Russia, as prologue to the world

socialist revolution, became the subject of all our discussions in

prison … Even behind bars, in a stuffy, stagnant cell, we felt instinctively

that the superficial calm that outwardly seemed to prevail presaged an

approaching storm … At last, on October 11, my turn [for release]

came … Stepping out of the prison on to the Vyborg-Side embankment and

breathing in deeply the cool evening breeze that blew from the river, I felt

that joyous sense of freedom which is known only to those who have learnt to

value it while behind bards. I took a tram at the Finland Station and quickly

reached Smolny … In the mood of the delegates to the Congress of Soviets

of the Northern Region which was taking place at that time .. an unusual

elation, an extreme animation was noticeable … They told me straightaway

that the CC had decided on armed insurrection. But there was a group of

comrades, headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev, who did not agree with this decision

and regarded a rising a premature and doomed to defeat.

(F.F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917, New York 1982, first

published 1925)

12 October

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to Russia

On [Kerensky] expressing the fear that there was a strong anti-Russian

feeling both in England and France, I said that though the British public was

ready to make allowances for her difficulties, it was but natural that they

should, after the fall of Riga, have abandoned all hope of her continuing to

take an active part in the war … Bolshevism was at the root of all the

evils from which Russia was suffering, and if he would but eradicate it he

would go down to history, not only as the leading figure of the revolution, but

as the saviour of his country. Kerensky admitted the truth of what I had said,

but contended that he could not do this unless the Bolsheviks themselves

provoked the intervention of the Government by an armed uprising.

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia, London 1923)

13 October

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Kerensky is becoming more and more unpopular, in spite of certain grotesque

demonstrations such as this one: the inhabitants of a district in Central

Russia have asked him to take over the supreme religious power, and want to

make him into a kind of Pope as well as a dictator, whereas even the Tsar was

really neither one nor the other. Nobody takes him seriously, except in the

Embassy. A rather amusing sonnet about him has appeared, dedicated to the beds

in the Winter Palace, and complaining that they are reserved for hysteria

cases … for Alexander Feodorovich (Kerensky’s first names) and then

Alexandra Feodorovna (the Empress).

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917–1918, London 1969)

14 October 2017

The BBC2 semi-dramatisation of how the Bolsheviks took power, shown this week,

was a curious thing. Talking heads in the form of Figes, Mieville, Rappaport,

Sebag-Montefiore, Tariq Ali, Martin Amis and others were interspersed with

moody reconstructions of late-night meetings, and dramatic moments such as

Lenin’s unbearded return to the Bolshevik CC (cf Sukhanov above). The programme

felt rather staged and unconvincing, with a lot of agonised expressions and

fist-clenching by Lenin, but the reviewers liked it. Odd, though, that

Eisenstein’s storming of the Winter Palace is rolled out every time, with a

brief disclaimer that it’s a work of fiction and yet somehow presented as

historical footage. There’s a sense of directorial sleight of hand, as if the

rather prosaic taking of the palace desperately needs a re-write. In some

supra-historical way, Eisenstein’s version has become the accepted version.

John Reed’s Ten Days that Shook the World

, currently being

serialised on Radio 4, is also presented with tremendous vigour, and properly

so as the book is nothing if not dramatic. Historical truth, though, is often

as elusive in a book that was originally published — in 1919 — with an

introduction by Lenin. ‘Reed was not’, writes one reviewer, ‘an ideal observer.

He knew little Russian, his grasp of events was sometimes shaky, and his facts

were often suspect.’ Still, that puts him in good company, and Reed is

undoubtedly a good read.