30 April - 6 May 1917

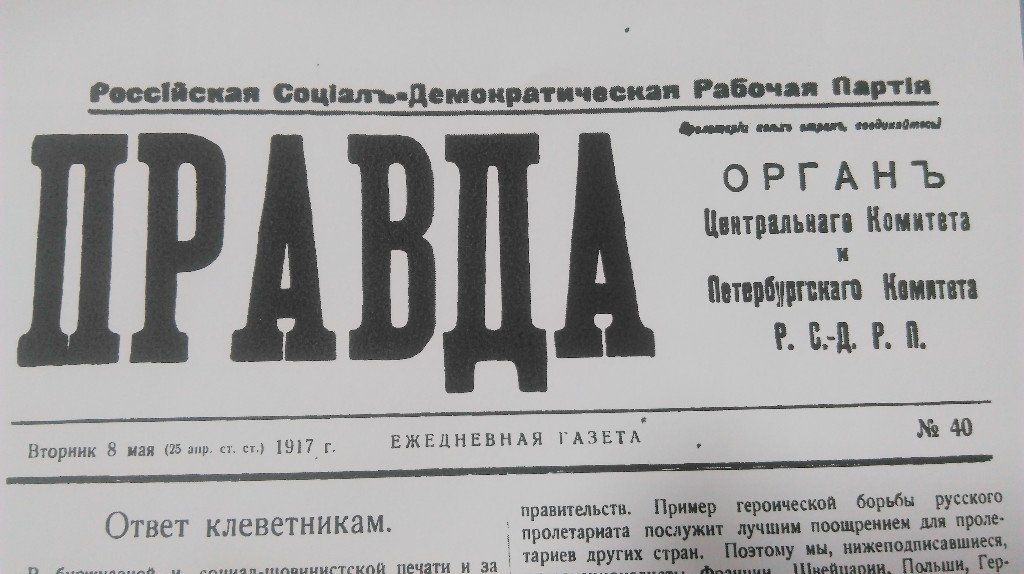

The Bolsheviks influenced minds mainly by means of the

printed word. By June, Pravda had a

run of 85,000 copies. They also put out provincial papers, papers addressed to

special groups (e.g. female workers and ethnic minorities), and a multitude of

pamphlets. They paid particular attention to the men in uniform … In the spring

of 1917 they distributed to the troops about 100,000 papers a day, which, given

that Russia had 12 million men under arms, was enough to supply one Bolshevik

daily per company … These publications spread Lenin’s message, but in a veiled

form … Such organisational and publishing activities required a great deal of

money. Much, if not most, of it came from Germany.

(Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution

, London 1995)

30 April

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

To summarise my acquaintance [with French ambassador

Paléologue] I will say that I judge him less than others … On a purely personal

basis I regret that I’m losing a pleasant, lively and amusing companion …

Moreover, he has a very low opinion of our government’s mindset, including

Kerensky. He has the impression that the Provisional Government is just a

continuation of hapless

Nicholas II. And therefore it’s the undoubted downfall of the first act of the

Russian Revolution.

(Alexander Benois ,

Diary 1916-1918

, Moscow 2006)

1 May

Article in The Times

Discussion of developments in Russia is still confined

rigidly in Germany to the Socialist Press. For weeks past the non-Socialist

organs, although they cannot conceal their excitement about the prospects of

the Stockholm plot, have published no serious comment on the Russian situation.

But they were moved to paroxysms of joy by the false report of the departure of

the British Ambassador from Petrograd. The Cologne

Gazette learned from Copenhagen that Sir George Buchanan left the British

Embassy secretly, ‘by a back-door’. The Munchner

Neuste Nachrichten reported from Berlin that the Ambassador had ‘made

himself impossible’ in Petrograd, and would not return. The Berliner Tageblatt, after expressing

some slight doubt as to the accuracy of the news, said: ‘The sudden departure

of the Ambassador is very natural. It is explained by his recognition that his

part is finished, and that there remains nothing for him to do on Russian soil,

since the policy pursued by him and, under his influence, by the Provisional

Government, has been shattered ... The English statesmen, unless they want to experience fresh

disasters, will have to send to the Neva a different Ambassador with quite

different instructions.’

('The Plot against Russia', The Times

)

A great impression has been produced here by General Brusiloff’s latest speech, which points out certain serious shortcomings in the Army and deplores the agitation for the conclusion of a premature peace, the relaxation of discipline, the number of deserters, and the tendency to fraternize with the enemy that has manifested itself since Easter. He stated that the enemy tempted the troops by offers of vodka, and endeavoured to deceive them by proclamations. He mentioned an instance in which the Russian artillery had prepared to fire on Germans advancing with vodka and white flags. He also dwelt on the numbers of deserters, who exercised a baneful influence in the rear, along the railways, and in the villages. He declared that lack of discipline must entail the ruin of Russia.

('Vodka and White Flags', The Times , from our own correspondent in the Balkan peninsula)

4 May

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Russia has slipped further down the dangerous slope.

Kerensky becomes Minister for War in the place of Guchkov. Milyukov is expected

to be replaced by Tereschenko. Nobody knows yet whether the other Kadets will

remain. The situation is serious: and the fact that Sazonov did not leave for

London clearly shows the change in Russian policy as it concerns the conduct of

the war. The worst is to be feared from Russia, who staged the revolution in

order to have peace, and who wants peace at any price … Several people coming

from Moscow and Kiev tell me that these two towns are as contaminated as

Petrograd. And yet, up to now there have been no serious disturbances in the

big centres. It is, rather, a slow disintegration. It is not the same in the

country districts. The soldiers charged with keeping order in the surroundings

of Orel have joined forces with the peasants. They have pillaged the stocks of

alcohol and have set fire to all the estates. The newspapers say that the

horizon is a red circle every night in this district.

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918

, London 1969)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov

By 2 o’clock in the morning of May 5th everything was ready. The portfolios have been quickly assigned, and all the doubtful points settled in this way: Kerensky got the War Ministry and the Admiralty, Pereverzev the Ministry of Justice; Peshekhonov Supply, Skobelev Labour, Tsereteli Posts and Telegraphs. The Coalition had been created. The formal union of the Soviet petty-bourgeois majority with the big bourgeoisie had been ratified in a written constitution … Now only the last act remained, the final chord, the apotheosis.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record , Oxford 1955)

Letter to the independent socialist newspaper Novaia zhizn

To All Russian Women and Mothers

We, a group of Russian women and mothers, are joining the

protest of the working people against the war. We are also extending our hand

to women and mothers the world over. We are deeply convinced that our extended

hand will meet the extended hands of mothers the world over. No annexations or

indemnities can compensate a mother for a murdered son. Enough blood. Enough of

this horrible bloodshed, which is utterly pointless for working people. Enough

of sacrificing our sons to the capitalists’ inflamed greed. We don’t need any

annexations or indemnities. Instead, let us safeguard our sons for the good of all

the working people the world over. Let them apply all their efforts not to a

fratricidal war but to the cause of peace and the brotherhood of all peoples.

And let us, Russian women and mothers, be proud knowing that we were the first

to extend our brotherly hand to all the mothers the world over.

Smolensk Initiative Group of Women and Mothers

(Mark D. Steinberg, Voices of Revolution, 1917

, New Haven and London 2001)

6 May

Declaration by the Second Provisional Government, published in Izvestiia

Reorganised and strengthened by the entrance of new representatives of the Revolutionary Democracy, the Provisional Government declares that it will resolutely and whole-heartedly put into practice the ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity - under whose banner the great Russian Revolution has come into being.

( Russian-American Relations March 1917-March 1920

, New York 1920)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

6 May 2017

This week's posting draws on several newspapers - German, Russian and British. In today's Guardian the novelist China Miéville muses on the relevance of the revolution for the world today. In fact he asks a very similar question to the one I put to Russian friends in St Petersburg a few weeks ago: how the government will mark the anniversary in October. 'Would it remember the centenary with celebration or anathema? "They will say there was a struggle," I was told, "and that eventually, Russia won."' He quotes the dissident Bolshevik Victor Serge, writing in 1937: 'It is often said that "the germ of all Stalinism was in Bolshevism at its beginning. Well, I have no objection. Only, Bolshevism also contained many other germs, a mass of other germs, and those who lived through the enthusiasm of the first years of the first victorious socialist revolution ought not to forget it. To judge the living man by the death germs which the autopsy reveals in the corpse - and which he may have carried in him since birth - is that very sensible?' Miéville makes an interesting point about the revolution turning in on itself: 'Without hope there's no drive to overturn an ugly world. Without pessimism, a frank evaluation of the difficulties, necessities can all too easily be recast as virtues. Thus after Lenin's death the party's adoption of Stalin's 1924 theory of "socialism in one country". This overturned a long commitment to internationalism, the certainty that the Russian revolution could not survive in isolation. The failure of the European revolutions provoked this - it was a shift born of despair. But announcing, ultimately celebrating, an autarchic socialism was a catastrophe. A hard-headed pessimism would have been less damaging than this bad hope.'