28 May - 3 June 1917

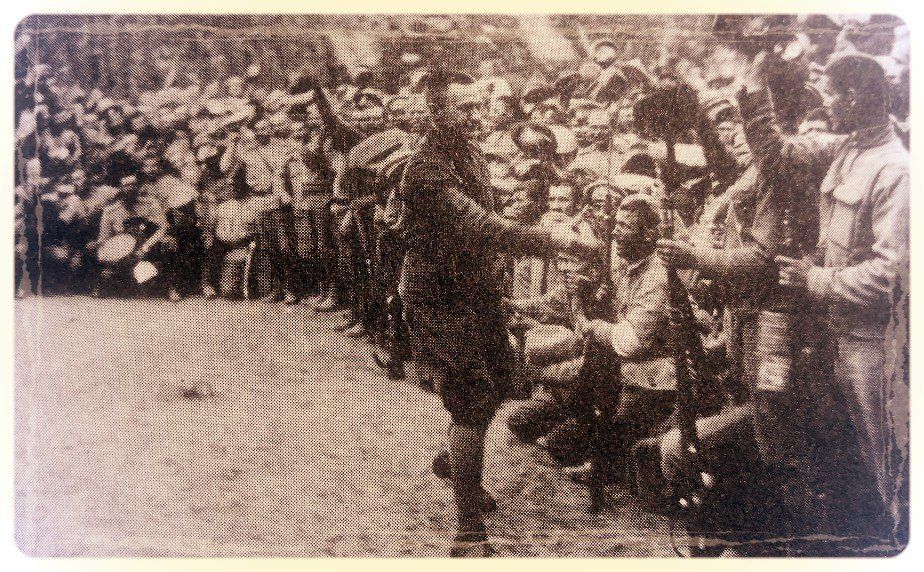

Kerensky visiting the front, summer 1917

An offensive was scheduled for mid-June. Kerensky’s personal

contribution to it consisted in rousing the troops with patriotic speeches;

these had an enormous immediate effect which evaporated as soon as he departed.

The generals, trying to command an increasingly undisciplined army, regarded

such rhetoric sceptically, dubbing the Minister ‘Persuader in Chief’. The will

to fight was no longer there. According to Kerensky, the Revolution had

persuaded the troops that there was no point in fighting. ‘After three years of

bitter suffering’, he recalled, ‘millions of war-weary soldiers were asking

themselves: “Why should I die now when at home a new, freer life is only

beginning?”’ The malaise was encouraged by the ambivalent attitude of the

Soviet, which continued to urge them to fight in the same breath that it

condemned the war as ‘imperialist’.

(Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution

, London 1995)

28 May

Article in the Sunday Times

This revolution is the most colossal social upheaval the world

has ever known. It has not fallen on a soil well prepared in advance, but has

fallen as a bombshell amongst 150 million of people, 80 per cent of whom are

ignorant peasants. It is hardly understood in this country that the revolution

is now the one paramount interest to the peasant’s mind, that the war occupies

but a very secondary place in his thoughts.

E. Ashmead Bartlett, ‘Our Task Ahead’, Sunday

Times

29 May

Diary entry of Joshua Butler Wright, Counselor of the American Embassy, Petrograd

Public opinion is as changeable as a summer day – and today

my British colleagues feel pessimistic as regards the socialists, who they say

are ‘agin’ everybody and prepared to make friends with no one.

( Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J. Butler Wright

, London 2002)

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

We went for a drive in a car through the immense

park [at Peterhof], where the roots of the great trees are bathed by the blue

waters of the Gulf of Finland. The park is filled with statues, colonnades,

pavilions, hermitages, kiosks, boskets, fountains, pools and water follies,

each one prettier than the last … Unfortunately, this splendid scene is defiled

by the crowds of soldiers who wander about, all unbuttoned and filthy,

sprawling on the lawns and grass walks and reading out their proclamations

under the colonnades … they were dressing on the terrace, whose marble

balustrades were hung with their thrown off clothes and their doubtful

underwear … the reign of the people is hardly an aesthetic one and when I saw

them I thought of how, in the past, in many of the towns of Russia there were

placards outside the park gates, forbidding the entry of ‘soldiers and dogs’.

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918

, London 1969)

1 June

By the first week of June it became clear that Kronstadt,

Tsaritzin and Krasnoyarsk were only Bolshevik islands. The rest of the country

was following the lead of the parties of compromise.

(M.P. Price, My Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution

, London 1921)

Memoir of Fedor Raskolnikov, naval cadet at Kronstadt

By June 1917 Kronstadt had been firmly mastered by our

Party. True, we did not have a majority even in the Soviet there, but the

actual influence of the Bolsheviks was, in essentials, unlimited … long before

the October Revolution, all power in Kronstadt was de facto in the hands of the

local Soviet – in other words, was held by our Party, which actually guided the

Soviet’s current activity.

(F.F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917

, New York 1982, first published 1925)

Emmeline Pankhurst arrived in Petrograd in early June 1917

‘with a prayer from the English nation to the Russian nation, that you may

continue the war on which depends the face of civilization and freedom’. She

truly believed, she insisted … ‘in the kindness of heart and the soul of

Russia’.

(Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution

, London 2017)

Letter from Sofia Yudina in Petrograd to her friend Nina Agafonnikova from Vyatka

We’ve just eaten, Lena has started practising [on the piano]

and I’ve gone to the studio. As soon as Lena finishes playing I will play. I

play three or four hours every day … In the evening it’s boring: the Toropovs aren’t here yet … we

haven’t been getting papers or letters for ages, and have no idea how to send

the letters we write … Papa’s and Mama’s moods are not good, and it’s very sad

and worse than anything, perhaps. The mood of the local peasants is fine and

sympathetic, for the moment this all seems peaceful. They seem to react to

events in a very sensible, sane way, as far as we can tell from talking to

them. They’re interested in how the revolution came about in Piter, what’s

happened to the tsar, where he is, what they’re now doing with him…

(Viktor Berdinskikh, Letters from Petrograd: 1916-1919

, St Petersburg 2016)

2 June

Report on a speech by the Russian Chargé

d'Affaires

In addressing you I am appealing to a certain portion of the

British people, who, after the war, will help Russia to rebuild the industrial

fabric of my country. I venture to say that of all the peoples allied for the

purpose of exterminating once and for all the poisonous gas of Prussianism, I

do not think that any two have manifested in a clearer and more striking manner

their deep-rooted desire for national and permanent friendship than Great

Britain and Russia. (Cheers.) They are allies not only in arms but in peace.

M. Nabokoff, Minister Plenipotentiary in charge of the

Russian Embassy in London, ‘Russia’s Duty to her Allies’, The Times

3 June

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman

Yalta. Princess Serge Dolgoruki died quite suddenly at the

age of thirty-six, leaving six children by a former husband – the eldest only

thirteen – and one little Dolgoruka. She has been unconscious for two days from

a mistaken dose of veronal. She is to be buried on Wednesday. She was a

charming lady, loved by everybody, and was an intimate friend of the Grand

Duchess Xenia. Her death has greatly upset us all.

( The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917

, New York 1919)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

3 June 2017

De Robien’s comments (29 May) about the ‘filthy’ and ‘unbuttoned’ soldiers at Peterhof are indicative of how much the Russian army had changed since the Revolution but they were only exercising their new privileges. An article by Robert Feldman (Soviet Studies, 1968) describes how quickly military authority broke down after the change of regime. The tsarist military code (articles 99, 100, 101, 102 and 104 to be precise) forbade the Russian soldier from smoking in the street, riding inside tramcars, frequenting clubs and public dances, and eating in restaurants or other places where drinks were sold. He wasn’t allowed to attend public lectures or theatrical performances, or even read books or newspapers without first having them vetted by his commanding officer. The Petrograd Soviet did away with these ‘degrading regulations’, giving soldiers complete civic freedom. This in turn alarmed the army’s high honchos, like Generals Ruzsky on the Northern Front and Alekseev, Chief of Staff, who pleaded with the new Minister of War Guchkov to prevent the ‘disease of disintegration’. Kerensky’s morale-raising tour of the front had only short-lived impact and by 1 June – just three weeks before a planned offensive against the Germans – he had replaced Alekseev along with the commanders of four of the five fronts. Feldman sums up the subsequent June offensive as dealing the Russian army ‘a blow from which it was never to recover’.