21-27 May 1917

- By Mark Sutcliffe

- •

- 27 May, 2017

- •

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov

There were indeed many excesses, perhaps more than before.

Lynch-law, the destruction of houses and shops, jeering at and attacks on

officers, provincial authorities, or private persons, unauthorized arrests,

seizures, and beatings-up – were recorded every day by tens and hundreds. In

the country burnings and destruction of country houses became more frequent.

The peasants were beginning to ‘regulate’ land-tenure according to their own

ideas, forbidding the illegal felling of trees, driving off the landlords’

stock, taking the stock of grain under their own control, and refusing to

permit them to be taken to stations and wharves.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record , Oxford 1955)

21 May

Diary entry of Joshua Butler Wright, Counselor of the American Embassy, Petrograd

Spring has suddenly turned into summer overnight – and the

trees are shooting forth green faster than any foliage I ever saw. It tempted

the ambassador and myself to the country to play golf in the afternoon – a poor

course but lovely country. My first glimpse of suburban life and found it

greatly resembles our western towns in many ways; ill kept small places, swarms

of children, log houses, etc. Surely among all the people that we saw in the

country and in the large parks of Petrograd there seemed no sign of anarchy or

violence. The people seemed rather to be emerging from a rather dazed state of

surprise at the complete liberty which they suddenly gained.

(Witness to Revolution: The Russian Revolution Diary and Letters of J. Butler Wright, London 2002)

Article in The Times

on the Labour conference in Leeds

Mr Ramsay MacDonald moved the first resolution,

congratulating the Russian people on a Revolution which had overthrown tyranny

… ‘We share,’ he added, ‘the aspirations of the Russian democracy. They turn to

us for counsel and support. Let us go to them and say “In the name of

everything you hold sacred, restrain the anarchy in your midst; find a cause

for unity, maintain your Revolution, stand by your principles, put yourselves

at the head of the democracies of Europe, give us inspiration so that you and

we together, shoulder to shoulder, will march out, bringing humanity still

further upward.’

‘Socialists on War Aims’, The Times

From the protocol of a general meeting of workers of the

Okulovsky Paper Factory and local peasants of Krestetsk Uezd, Novgorod

Province, 21 May 1917

Let our socialist comrades in the Ministry as well as in the

Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies know that even in the

remote provinces we hear their summons to save free Russia and know their work

and devotion to the people and with them burn with the desire to work for the

common goal –the Salvation of Free Democratic Russia.

(Mark D. Steinberg, Voices of Revolution, 1917, New Haven and London 2001)

22 May

On the 22nd

[Lenin] addressed the delegates [of the First All-Russian Congress of Peasants’

Soviets] in person, hammering home his support for the poorest peasants and

demanding the redistribution of land.

(ChinaMiéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution, London 2017)

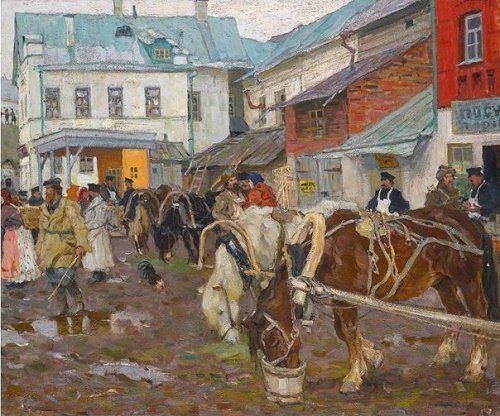

The opening

day of this first Labour Parliament of Russia was very memorable. From an early

hour in the morning the corridors and halls of the Naval Cadet Corps in the

Vassily Ostroff were filled with delegates arriving from East and West. Each

group as it arrived bore the mark of the region from which it hailed. Here was

a picturesque group of Ukrainians round a samovar and an accordion. There was a

group of sunburnt soldiers from the garrisons in Central Asia. There were some

dark-eyed natives from the Caucasus. There were lusty soldiers from the trenches,

and serious-looking officers; there were artizans from the Moscow factories and

mining representatives from the Don.

(M.P. Price, My Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution, London 1921)

24 May

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Kerensky

has occasional bursts of energy and is trying to take the army in hand again:

he has reorganized the courts-martial and ordered them to severely punish all

attempts at desertion. All requests to resign presented by officers are refused

and General Gurko, who, because of the growing lack of discipline has asked to

be relieved of his command of the central group of armies, has been put at the

head of a mere division. Generalissimo Alexeiev has been replaced by General

Brussilov, the victor of Galicia. But what can all these measures accomplish

against the forces of anarchy which are causing the army to disintegrate, and

against which all words are useless?

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917-1918, London 1969)

Diary entry of an anonymous Englishman

Felix

Yusupov and his wife to tea in the loggia. Afterwards, in the garden, he told

me the whole story of the murder of Rasputin.

(The Russian Diary of an Englishman, Petrograd 1915-1917, New York 1919)

25 May

Letter from Sofia Yudina in Petrograd to her friend Nina Agafonnikova in Vyatka

Today the

weather is fine: sky as blue as blue, white clouds. I’m sitting by the open

window: the lightest of breezes, the smell of the garden, the long grass gently

moving, the ceaseless chirping of the birds – the warblers and chaffinches. And

so many nightingales at night! And frogs!.. Mama is tired from the journey,

Papa is okay, feels fine, just worried by the chaos in our household. Lena

doesn’t know where to put herself, she’s reading Tolstoy’s ‘War and Peace’. We

don’t hear a word from her.

(Viktor Berdinskikh, Letters from Petrograd: 1916-1919, St Petersburg 2016)

26 May

Article in The Times

When Russia

stepped forth from her prison she stepped into Utopia, and she has not yet

discovered that it is Utopia. All this is quite natural, but it is embarrassing

and dangerous. If it be not corrected Russia will fall away from the great

Alliance against barbarism or will stultify the Alliance by an inadequate

peace. Our difficulty is Germany’s opportunity, and she has not been slow to

use her opportunity. Into the Russian lines German aeroplanes have dropped multiplied

forgeries. These purport to be copies of letters from Russian homes to Russian

soldiers – letters which fell into German hands when the soldiers to whom they

were addressed become prisoners of war. Here is one of those forgeries: –'Dear

Soldiers, – You ought to know that Russia would have concluded peace long ago

had it not been for England, but we want peace – we are thirsting for it.

Working men, who have now the opportunity of making their wishes known, are

demanding peace. Nobody has the right to say that the Russian workman is

against peace. England has no right to say that. Whatever the outcome of this

evil war, we cannot expect any gratitude from England. Therefore we must shake

ourselves free of England. This is the demand of the people. This is its holy

will. I have nothing more to write. I am well, and hope the same of you. Your

loving brother, Nicolai'.

('The New Russia: From Prison into Utopia' by C. Hagberg Wright, The Times)

27 May

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

I've recently become indifferent to everything. An elemental tragedy is almost certain to be played out, and what its outcome will be, nobody for the moment can say.

(Alexander Benois, Diary 1916-1918, Moscow 2006)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

27 May 2017

Narodnaya volya (People’s Will) was the revolutionary

organisation behind the assassination of Alexander II in 1881 and many other

terrorist acts in the decades leading up to the 1917 Revolution. Lenin’s

brother, Alexander Ulyanov, was involved with one of its subsequent

incarnations, and was hanged at the age of seventeen. Lenin’s ferocious

commitment to overthrowing the tsarist regime has often been ascribed to this

event, an extreme example, perhaps, of unintended consequences.

In the week of the Manchester bombing, it would be wrong to equate Russia’s revolutionary movement with Islamist fanaticism, the one committed to the demise of a brutal authoritarian government, the other blindly waging war against those who enjoy the freedoms of democratic government. But lessons of unintended consequences are often ignored by those in power, and it can be important to take a step back. The instinct of people to come together, to look for mutual reassurance and seek out the good in the face of inexplicable horror, was witnessed in the vigil in Manchester’s Albert Square, and in particular Tony Walsh’s poem ‘This is the Place’ – a stirring tribute to the city’s contribution to the world, an acknowledgement of the hurt, but most of all a reminder that people coming together, and working together, can create a place where a Muslim man supports his elderly Jewish neighbour as they stand united in grief.

8 October

Letter from Lenin to the Bolshevik Comrades attending the Regional Congress of

the Soviets of the Northern Region

Comrades, Our revolution is passing through a highly critical period …

A gigantic task is being imposed upon the responsible leaders of our Party,

failure to perform which will involve the danger of a total collapse of the

internationalist proletarian movement. The situation is such that verily,

procrastination is like unto death … In the vicinity of Petrograd and in

Petrograd itself — that is where the insurrection can, and must, be decided on

and effected … The fleet, Kronstadt, Viborg, Reval, can and must advance

on Petrograd; they must smash the Kornilov regiments, rouse both the capitals,

start a mass agitation for a government which will immediately give the land to

the peasants and immediately make proposals for peace, and must overthrow

Kerensky’s government and establish such a government. Verily, procrastination

is like unto death.

(V.I. Lenin and Joseph Stalin, The Russian Revolution: Writings and Speeches

from the February Revolution to the October Revolution, 1917, London 1938)

9 October

Report in The Times

The Maximalist [Bolshevik], M. Trotsky, President of the Petrograd Soviet,

made a violent attack on the Government, describing it as irresponsible and

assailing its bourgeois elements, ‘who,’ he continued, ‘by their attitude are

causing insurrection among the peasants, increasing disorganisation and trying

to render the Constituent Assembly abortive.’ ‘The Maximalists,’ he declared,

‘cannot work with the Government or with the Preliminary Parliament, which I am

leaving in order to say to the workmen, soldiers, and peasants that Petrograd,

the Revolution, and the people are in danger.’ The Maximalists then left the

Chamber, shouting, ‘Long live a democratic and honourable peace! Long live the

Constituent Assembly!’

(‘Opening of Preliminary Parliament’, The Times)

10 October

As Sukhanov left his home for the Soviet on the morning of the 10th, his

wife Galina Flakserman eyed nasty skies and made him promise not to try to

return that night, but to stay at his office … Unlike her diarist husband,

who was previously an independent and had recently joined the Menshevik left,

Galina Flakserman was a long-time Bolshevik activist, on the staff of Izvestia.

Unbeknownst to him, she had quietly informed her comrades that comings and

goings at her roomy, many-entranced apartment would be unlikely to draw

attention. Thus, with her husband out of the way, the Bolshevik CC came

visiting. At least twelve of the twenty-one-committee were there … There

entered a clean-shaven, bespectacled, grey-haired man, ‘every bit like a

Lutheran minister’, Alexandra Kollontai remembered. The CC stared at the

newcomer. Absent-mindedly, he doffed his wig like a hat, to reveal a familiar

bald pate. Lenin had arrived.

(China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution, London 2017)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai

Sukhanov

Oh, the novel jokes of the merry muse of History! This supreme and decisive

session took place in my own home … without my knowledge … For such a

cardinal session not only did people come from Moscow, but the Lord of Hosts

himself, with his henchman, crept out of the underground. Lenin appeared in a

wig, but without his beard. Zinoviev appeared with a beard, but without his

shock of hair. The meeting went on for about ten hours, until about 3 o’clock

in the morning … However, I don’t actually know much about the exact

course of this meeting, or even about its outcome. It’s clear that the question

of an uprising was put … It was decided to begin the uprising as quickly

as possible, depending on circumstances but not on the Congress.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record, Oxford 1955)

11 October

British Consul Arthur Woodhouse in a letter home

Things are coming to a pretty pass here. I confess I should like to be out

of it, but this is not the time to show the white feather. I could not ask for

leave now, no matter how imminent the danger. There are over 1,000 Britishers

here still, and I and my staff may be of use and assistance to them in an

emergency.

(Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917, London 2017)

Memoir of Fedor Raskolnikov, naval

cadet at Kronstadt

The proximity of a proletarian rising in Russia, as prologue to the world

socialist revolution, became the subject of all our discussions in

prison … Even behind bars, in a stuffy, stagnant cell, we felt instinctively

that the superficial calm that outwardly seemed to prevail presaged an

approaching storm … At last, on October 11, my turn [for release]

came … Stepping out of the prison on to the Vyborg-Side embankment and

breathing in deeply the cool evening breeze that blew from the river, I felt

that joyous sense of freedom which is known only to those who have learnt to

value it while behind bards. I took a tram at the Finland Station and quickly

reached Smolny … In the mood of the delegates to the Congress of Soviets

of the Northern Region which was taking place at that time .. an unusual

elation, an extreme animation was noticeable … They told me straightaway

that the CC had decided on armed insurrection. But there was a group of

comrades, headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev, who did not agree with this decision

and regarded a rising a premature and doomed to defeat.

(F.F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917, New York 1982, first

published 1925)

12 October

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to Russia

On [Kerensky] expressing the fear that there was a strong anti-Russian

feeling both in England and France, I said that though the British public was

ready to make allowances for her difficulties, it was but natural that they

should, after the fall of Riga, have abandoned all hope of her continuing to

take an active part in the war … Bolshevism was at the root of all the

evils from which Russia was suffering, and if he would but eradicate it he

would go down to history, not only as the leading figure of the revolution, but

as the saviour of his country. Kerensky admitted the truth of what I had said,

but contended that he could not do this unless the Bolsheviks themselves

provoked the intervention of the Government by an armed uprising.

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia, London 1923)

13 October

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Kerensky is becoming more and more unpopular, in spite of certain grotesque

demonstrations such as this one: the inhabitants of a district in Central

Russia have asked him to take over the supreme religious power, and want to

make him into a kind of Pope as well as a dictator, whereas even the Tsar was

really neither one nor the other. Nobody takes him seriously, except in the

Embassy. A rather amusing sonnet about him has appeared, dedicated to the beds

in the Winter Palace, and complaining that they are reserved for hysteria

cases … for Alexander Feodorovich (Kerensky’s first names) and then

Alexandra Feodorovna (the Empress).

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917–1918, London 1969)

14 October 2017

The BBC2 semi-dramatisation of how the Bolsheviks took power, shown this week,

was a curious thing. Talking heads in the form of Figes, Mieville, Rappaport,

Sebag-Montefiore, Tariq Ali, Martin Amis and others were interspersed with

moody reconstructions of late-night meetings, and dramatic moments such as

Lenin’s unbearded return to the Bolshevik CC (cf Sukhanov above). The programme

felt rather staged and unconvincing, with a lot of agonised expressions and

fist-clenching by Lenin, but the reviewers liked it. Odd, though, that

Eisenstein’s storming of the Winter Palace is rolled out every time, with a

brief disclaimer that it’s a work of fiction and yet somehow presented as

historical footage. There’s a sense of directorial sleight of hand, as if the

rather prosaic taking of the palace desperately needs a re-write. In some

supra-historical way, Eisenstein’s version has become the accepted version.

John Reed’s Ten Days that Shook the World

, currently being

serialised on Radio 4, is also presented with tremendous vigour, and properly

so as the book is nothing if not dramatic. Historical truth, though, is often

as elusive in a book that was originally published — in 1919 — with an

introduction by Lenin. ‘Reed was not’, writes one reviewer, ‘an ideal observer.

He knew little Russian, his grasp of events was sometimes shaky, and his facts

were often suspect.’ Still, that puts him in good company, and Reed is

undoubtedly a good read.