29 January - 4 February 1917

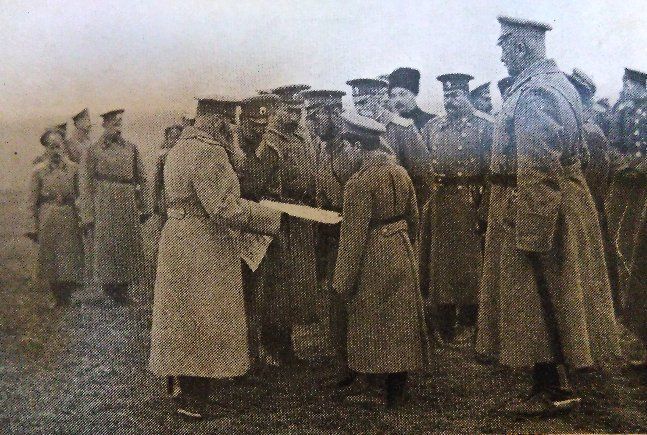

Nicholas II and the Tsarevich Aleksei on the South-West Front

Spring 1916

On the eve of the Revolution the prospects for the 1917 campaign were brighter than they had been in March 1916 ... The Russian infantry was tired, but less tired than it had been twelve months earlier. It was evident that the Russian Command must in future squander men less lavishly on the front, but still the depots contained 1,900,000 men, and 600,000 more of excellent material were joining from their homes ... There can be no doubt that if the national fabric had held together, or, even granted the Revolution, if a man had been forthcoming who was man enough to protect the troops from pacifist propaganda, the Russian army would have gained fresh laurels in the campaign of 1917, and in all human probability would have exercised a pressure which would have made possible an allied victory by the end of the year.

(Major-General Sir Alfred Knox, With the Russian Army 1914-1917

, London 1921)

29 January

Diary entry of Lev Tikhomirov, revolutionary and later conservative thinker

I’m worse

again. Temperature’s gone up … In Moscow

there’s a shortage of flour and bread. The city chief administrator has

announced that his reserves have run out as well and asks the people to be

patient. It wasn’t long – a week at most – since he was fining bakers for not

requesting flour from his reserves! What a ridiculous situation. The bakers are

calling him every name under the sun, saying that he’s bought up all the flour

on the cheap and is now ‘giving it by the

pood

[16 kilos] to his cronies!’ I’m sick to death of all this. As though the chief

administrator has thousands of cronies! A veritable tower of Babel. Meanwhile

‘the representatives of the allied nations’ are banqueting with representatives

of our ‘society’ and making joint declarations about our impending victory.

Milner

[head of British delegation to Russia] has also been

describing how the English will build up our industry. Of course they will,

just as they’re doing in India!

(L.A. Tikhomirov, Diary 1915-1917

, Moscow 2008)

Letter from

Aleksei Peshkov [Maxim Gorky] to his wife E.P. Peshkova, from Petrograd

I very much

advise against your coming here, Katia! … The situation is critical. If

transport stops for two weeks, famine will set in. There’s already no flour

here. The session of the Duma probably won’t open on the 14th, although all

manner of turmoil could occur on that day … Things here in general are alarming

and grim, and there would be nothing for you to do. I’m giving a reading on the

first. It will be a success. Zinovii Peshkov

[Gorky’s godson] has been promoted

to lieutenant, he has been sent by the French to America and is getting forty

dollars a day! He’s having an affair with Countess Chernikh, wife of the

Sarajevan consul, the one who aided the Austrian plot against Serbia. The

countess, who is English by birth, asked her husband for a divorce when the war

began, and now Zinovii’s turned up! … Aleksei Peshkov is working like an ox.

I’ve caught a cold, I’ve lost my voice, I’m sneezing, and I’m afraid that I

won’t get better by the first! But that’s nothing! Everything here is

abominable. I say this to you not by way of consolation, but just because

that’s how it is.

Keep well!

A

( Maksim Gorky: Selected Letters

, Oxford 1997)

Sunday Times article headed 'The Petrograd Conference: Russia's Peace Aims'

The Conference of the Allies in Petrograd is surrounded by mystery. Nothing official has transpired. However, it is an open secret that what the Conference is discussing is the future map of Europe. Everybody realises that the war has entered on its last stage. Everybody in Russia is confident of victory, even if to attain it a fight with the Government should become necessary.

( Sunday Times

, 'From our own correspondent, Petrograd')

30 January

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

A meeting

with the Hermitage at 11, this time in the museum itself. All Hermitage people.

Everyone extremely pleasant to me, from the director Dm. Iv. Tolstoi down.

Seems they’ve decided to draw a veil over my article last year

[about poor

restoration of museum’s paintings] . Iskersky

[curator] once again revealed a

surprising degree of ignorance. The question of what to do with the large

paintings at Gatchina Palace was also discussed. They include a huge forest

landscape with figures, showing the ‘Flight into Egypt’ (Lipgart

[curator of

paintings] claims that it’s an early Titian! I’m more inclined to attribute it

to Domenico Campagnola) … These paintings were taken to the Hermitage

temporarily for restoration, but they would like to ‘incorporate’ them. Will

the Dowager Empress

[Maria Feodorovna] agree to this? After all, she is

fundamentally opposed to any changes to Gatchina’s artistic ensemble: ‘As it

was under the late Sovereign, so it must remain!’ … Lunched with Argutinsky

[collector] at Café Donon. Two of our elegant diplomats – Savinsky and Prince

Urusov – came and sat with us. This quite spoilt it for me, as they blathered

on the whole time, either about the war, or mutual acquaintances, or about the

Allies. And a table away from us were two of the most typical Jews imaginable,

with predatory faces, discussing with gusto their (no doubt dark) affairs. It

seemed very clear who now holds the cards, who is generally ‘master of the

situation’, and into whose hands the present critical state of affairs will

play.

(Alexander Benois ,

Diary 1916-1918

, Moscow 2006)

31 January

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

Eleven workmen,

members of the Central Committee of Military Industries, have just been

arrested on a charge of ‘plotting a revolutionary movement with the object of

proclaiming a republic’. Arrests of this kind are common enough in Russia, but

in the ordinary way the public hears nothing about them. After a secret trial,

the accused are sent to a state gaol or banished to the depths of Siberia. The

press never mentions the matter, and quite frequently even their families do

not know what has happened to their missing relative. The silence in which

these summary convictions are wrapped has a good deal to do with the tragic

notoriety of the

Okhrana . But this

time the element of mystery has been dispensed with. A sensational communiqué informs the press of the

arrest of the twelve workmen. This is Protopopov’s way of showing how busy he

is in saving tsarism and society.

(Maurice Paléologue,

An Ambassador's Memoirs 1914-1917

, London 1973)

1 February

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

Visit from

Scamoni

[printer] again. He is convinced there won’t be any serious

disturbances, only some isolated and fruitless strikes resulting from specific

harassment of workers. But he’s basing his judgement on the business he runs –

and the Golike-Vyborg printing house is run on far more cultured lines than

many other, bigger enterprises. Their workers, it seems, are happy with their

situation, which has greatly improved in recent times. ‘Their doorkeeper now

earns more than the typesetter used to’.

(Alexander Benois ,

Diary 1916-1918

, Moscow 2006)

2 February

Diary entry of James L. Houghteling, Jr, attaché at the American Embassy, Petrograd

This is a

church holiday, and G. and I went out to Lyubertsi, the Harvester Company’s

industrial town ten miles out, to ski with the Varkalas … The travelling was

up-hill and down-dale but the snow was fairly hard and the air clear and

exhilarating. We came to no fences nor boundary marks till we neared the

monastery … After an hour we came out on the top of steep slopes above the

valley of the Moskva River … Here we had glorious coasting, so good that we

climbed up and tried again. On the second trip down, I carelessly raised one

foot and had the pleasure of seeing my ski dash off down the hill ahead of me.

Of course I had a beautiful fall and the rest of the slide was a mélange of

hopping, tripping and bad language.

(James L. Houghteling, Jr, A Diary of the Russian Revolution

, New York 1918)

4 February

Letter from Nicholas II to his cousin George V

My dearest Georgie,

I thank you very much for your kind long letter. I entrust mine to the care of Lord Milner, whose acquaintance I was very pleased to make. Twice I had the occasion of seeing all the members of your mission. I hope they will return safely to England – the journey has become now still more risky since those d--d pirates sink every ship they can only get hold of. In a couple of days the work of the Conference will come to an end. May its results be fruitful and of useful consequences for both our countries and for all the Allies. The weak state of our railways has since long preoccupied me. The rolling stock has been and remains insufficient and we can hardly repair the worn out engines and cars, because nearly all the manufactories and fabrics of the country work for the army. That is why the question of transport of stores and food becomes acute, especially in winter, when the rivers and canals are frozen. Everything is being done to ameliorate this state of things which I hope will be overcome in April. But I never lose courage and egg on the ministers to make them and those under them work as hard as they can. But whatever the difficulties may be yet in store for us – we shall go on with this awful war to the end.

Alix and I send May and your children our fond love.

With my very best wishes for your welfare and happiness. Ever my dearest Georgie, your most devoted cousin and friend,

Nicky

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion

, London 1996)

Diary entry of Lev Tikhomirov, revolutionary and later conservative thinker

Moscow is

dark, they’re not lighting the lamps. So of course the robbers are having a

field day. What a difficult time! It’s not just the maid who’s barely

surviving, even the cat Barsik has got as thin as a skeleton. There’s nothing

to eat – he eats potato. Today I gave Masha 40 kopecks to buy him some offal.

He loves it but when there’s nothing to buy, there’s nothing to give him. He’s

already polished off every mouse going. Poor old cat.

(L.A. Tikhomirov, Diary 1915-1917

, Moscow 2008)

4 February 2017

A review in the Guardian of the Royal Academy's Revolution exhibition that's due to open next weekend. In fact the article takes issue with the title rather than the exhibition, which the reviewer hasn't yet seen, and whether it's right to be celebrating revolutionary art in this way – art that glorifies the victory of a regime achieved through terrible bloodshed. Not sure I agree with the premise, but it got me thinking about contemporary Russian or earlier Soviet attitudes to the seismic events of 1917. It's easy (particularly for students of Russian art and literature) to be misty-eyed about a revolution that forged the work of poets and artists such as Mayakovsky, Stepanova and Rodchenko in its fire; less so perhaps for those who lived with the consequences. Dmitry Furman, who died in 2011, has been described as 'a scholar ... who joined political integrity and intellectual originality in a body of work that addressed the fate of his country, and the past of the world, in ways that were equally and strikingly passionate and dispassionate'. In response to the 'what ifs', the different paths Russia could have taken in the early twentieth century, Furman wrote this: 'This was, in the end, our revolution, engendered by our culture. In countries with a cultural tradition such as that of England, the USA or the Netherlands, this kind of revolution would be essentially impossible. With us, though, powerful forces were pushing us towards it, forces linked to internal cultural factors that were specifically ours: the cultural rift between the top and bottom of society; the 'westernized' orientation of the intelligentsia and its desire ... not just to catch up with the West but surpass it and make Russia the lodestar for the whole world; the inflexibility of a political and ideological structure that made gradual, evolved development almost impossible; and the archaic mindset of the popular masses, who could only grasp revolutionary ideology in a quasi-religious form. Maybe there could have been other other ways, perhaps less bloody, perhaps more so, but to imagine that if 1917 hadn't happened Russia would have developed peacefully and quickly, and would now be some kind of USA-equivalent – it's virtually impossible.'