26 February - 4 March 1917

- By Mark Sutcliffe

- •

- 03 Mar, 2017

- •

Революция \ Revolution!

The February Revolution came like a thief in the night. How

often had its possibility been discussed in Russia during the two and a half

years that followed the outbreak of the Great War! Over samovars and

tea-glasses officers and students had speculated whether it would come during

the war or after peace. Working men had whispered of it in traktirs [taverns] with bated

breath. Soldiers had timidly broached the subject to each other in the

trenches. When at last it came, nobody seemed quite to know what had happened.

In the distant provinces the wildest rumours were circulating. The Petrograd

workmen had made it, said one, and they did not represent the true Russia. The

Revolution was made by a people, exasperated by a pro-German Tsar, to enable

the war to be prosecuted with greater vigour, said a second. It was the

unmistakable sign of a patriotic revival, said a third. It was the beginning of

chaos, said a fourth.

(M. Philips Price, former correspondent of the Manchester

Guardian in Russia, My Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution, London 1921)

26 February

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

As I was returning from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs this morning, I met one of the leaders of the Cadet Party, Basil Maklakov. ‘We’re in the presence of a great political movement now,’ he said. ‘Everyone has finished with the present system. If the Emperor does not grant the country prompt and far-reaching reforms, the agitation will develop into riots. And there is only a step between riot and revolution.’

(Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs 1914-1917, London 1973)

Letter from Nicholas to Alexandra in Tsarskoe Selo

This morning during service I felt an excruciating pain in the middle of my chest, wh. lasted for a quarter of an hour. I could hardly stand & my forehead was covered with beads of sweat. I cannot understand what it was, as I had no heart beating, but it came & left me at once, when I knelt before the Virgin’s image! … I hope Khabalov [military governor of Petrograd] will know how to stop those street rows quickly. Protopopov ought to give him clear & categorical instructions … God bless you, my Treasure, our children & her [Anna Vyrubova]! I kiss you all tenderly. Ever your own Nicky.

(The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra: April 1914-March 1917, ed. Joseph T. Fuhrmann, London 1999)

Nicholas, who continued to receive soothing reports from

Protopopov, had no idea how charged the situation in the capital had become. It

seemed intolerable to him that while the troops at the front braved hardships

and faced the prospect of death, civilians in the rear should be rioting … On

Sunday morning, February 26, troops in combat gear occupied Petrograd and all

seemed back to normal. But it only seemed so. For on that day an incident

occurred that completely transformed the situation.

(Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, London 1995)

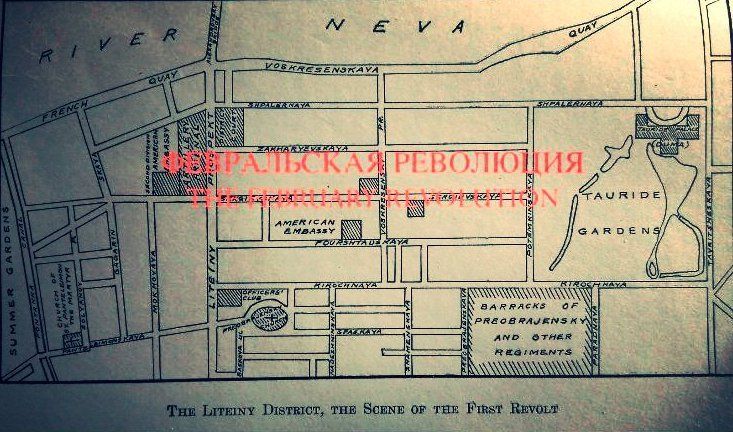

In the early evening the ‘most sanguinary episode in the

Revolution’ ... had occurred at Znamensky Square, where a dense mass of people

from the Nevsky had converged with another crowd coming up Ligovskaya, the

major thoroughfare to the south of the square. ‘Local police leaders on

horseback rode among the crowd ordering them home,’ recalled Dr Joseph Clare, pastor

of the American Church, who witnessed the scene. ‘The people knew the soldiers were

on their side and refused to move.’ Lined up in front of a hotel facing the

square were men from the 1st and 2nd training detachments of the Volynsky

Regiment. When their commander ordered them to disperse the crowd, the soldiers

begged the crowds to move on, so they would not have to use their weapons, but

the people refused to budge. Angrily the officer had one of the reluctant

soldiers arrested for insubordination and again ordered his men to fire. ‘They

shot in the air, and the officer got mad, making each individual fire into the

mob.’ Finally he raised his own pistol and started firing into the crowd. Then

‘suddenly came the rat-tat-tat of a machine-gun. The people could hardly

believe their ears, but there was no doubting the evidence of eyes as they saw

people falling … [then] something extraordinary happened: the troop of Cossacks

positioned in the square had turned and fired at the gunners on the house tops

… the crowd scattered behind buildings and courtyards, from where some of them

began firing at the military and police. Forty or so were killed and hundreds

wounded.

(Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917, London 2016)

Sergei Kirpichnikov, young sergeant in the Volynsky Regiment

I told [my fellow conscripts] that it would be better to

die with honour than to obey any further orders to shoot at the crowds: ‘Our

fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers, and brides are begging for bread’, I said. ‘Are we going to kill them? Did you see the blood on the streets today? I say

we shouldn’t take up positions tomorrow. I myself refuse to go.’ And, as one,

the soldiers cried out: ‘We shall stay with you!’

(Orlando Figes, A People's Tragedy, London 1996)

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

Everyone is extremely tense and nobody is under any illusion as to the success of the

revolutionary movement. It seems more likely that the police and their bayonets

will crush the mutiny. But in any case we can now speak about a mutiny as

something that has already taken place.

(Alexander Benois, Diary 1916-1918, Moscow 2006)

27 February

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov

The

unforgettable 27th of February came … The popular revolution was going ahead at

full steam, making hourly changes in the entire political situation, upsetting

the ‘combinations’ of the liberals, generals, and plutocrats, and dragging

along in its wake the Duma as the political centre of the bourgeoisie … What

the Tsarist command did in those hours, what ‘measures’ it conceived of or put

into practice for the struggle against the revolution, I neither know nor

remember. Who cares anyhow? No one in Petersburg could have doubted any longer

that the Tsarist authorities could not influence the course of events in any

way.

(The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record by N.N. Sukhanov,

Oxford 1955)

Diary entry of James L. Houghteling, Jr, attaché at the American Embassy, Petrograd

Last night

when I got on the train in Moscow, I found my reservation in a compartment with

two men and a woman (or lady, I may fairly say). The train left at midnight; my

ticket entitled me to one of the lowers and the lady sat in the other while a

peasant of shop-keeper type dropped off to sleep in the upper above her. I

removed collar, coat, and shoes, wrapped myself in my overcoat and prepared for

sleep. Then the lady skillfully climbed a ladder and leaped into the other

upper. Thus perfectly naturally and decorously we travelled together. Next

morning we all conversed and a third man who proved to be a clerk for the

Russian-American Chamber of Commerce produced some chewing-gum, which was an

amusing novelty to the lady and the peasant. At the Nikolaieff Station in

Petrograd the porter told me there were no svoshchiks. When I reached the front

of the station, I knew instinctively that the revolution had begun. Not a

vehicle in sight, except a stray truck-sledge or two, not a street-car on that

usually busy square; only the people standing amazed on the sidewalks and a

patrol of Cossacks riding placidly around the snow-covered road-way. A workman

came and explained, and then showed me by gestures, that there had been

shooting.

(James L. Houghteling, Jr, A Diary of the Russian Revolution, New York 1918)

Diary entry of Lev Tikhomirov, revolutionary and later conservative thinker

Surprising

news has been received (from two different sources) from Petrograd. It seems

the State Duma has been dissolved but the Duma hasn’t dispersed and a military

mutiny has erupted in its defence. Three or four Guard regiments have seized

the Arsenal and apparently the Peter and Paul Fortress too, and they’re

guarding the Duma. Seems that Golitsyn has resigned, and Protopopov has rushed

off to Tsarskoe Selo. Looks like some kind of committee has been formed under

the chairmanship of Rodzianko. Terrifying news, if it is true. How will it end?

I’m worried for our Kolya too. Who knows whether he’ll be dragged into putting down

the mutiny or be forced to fight with the mutineers. Which is worse? One thing

for sure, the situation is desperate … And how typical: on 22nd February the Tsar

heads to the front, by the 24th ‘bread’ demonstrations are starting, and on the 27th we

have a military pronunciamento

[coup]. A clear conspiracy. But it would be good

to know what it’s trying to achieve. What do they want to do?

(L.A. Tikhomirov, Diary 1915-1917, Moscow 2008)

Memoir of Princess Paley

On the

Monday, February 27th, the total absence of all newspapers made us fear the

worst. At Tsarskoe we lacked nothing, but in St Petersburg there was a shortage

of bread … My daughters telephoned from the capital that the firing was growing

worse and worse, and that some of the regiments were beginning to join the

rioters. Towards two o’clock there arrived from Petrograd a certain Ivanoff, a

notary’s clerk, a young man of great intelligence, brave and ambitious … ‘All

is not lost,’ he declared. ‘If the Emperor would but mount a white horse at the

Narva Gate and make a triumphant return into the town, the situation would be

saved. How can you remain quietly here?’

(Princess Paley, Memories of Russia, 1916-1919, London 1924)

Letter from Nicholas to Alexandra in Tsarskoe Selo

My own

Treasure!

Tender

thanks for your dear letter. This will be my last one. How happy I am at the

thought of meeting you in two days. I had much to do & therefore my letter

is short. After the news of yesterday from town I saw many faces here with

frightened expressions.

(The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra: April 1914-March 1917, ed. Joseph T. Fuhrmann, London 1999)

28 February

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

… a day

which has been prolific in grave events and may perhaps have determined the

future of Russia for a century to come.

(Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs 1914-1917, London 1973)

1 March

Letter from Aleksei Peshkov [Maxim Gorky] to his wife E.P. Peshkova, from Petrograd

The events taking place may appear grandiose,

even moving at times, but their meaning is not so profound and sublime as

everyone imagines. I am filled with skepticism, even though I am also moved to

tears at the sight of soldiers marching to the State Duma to the sound of

music. I don’t believe in a revolutionary army; I think that many people are

mistaking an absence of organization and discipline for revolutionary activity.

All the forces in Petersburg have gone over to the Duma, that’s true; so have

the units coming from Oranienbaum, Pavlovsk and Tsarskoe. But the officers

will, of course, side with Rodzianko and Miliukov up to a certain point, and

only the wildest dreamer would expect the army to stand together with the

Soviet of Workers’ Deputies. The police, ensconced in attics, spray the public

and soldiers with machine-gun fire. Cars packed with soldiers and bearing red

flags drive around the city in the search for policemen in disguise, and these

are then placed under arrest. In some cases they are killed, but for the most

part they are brought to the Duma, where about 200 policemen out of 35,000 have

already been rounded up. There’s a great deal of absurdity – more than there is

of the grandiose. Looting has begun. What will happen next? I don’t know But I

see clearly that the Kadets and the Octobrists are turning the revolution into

a military coup. Will they succeed? It seems they already have. We won’t turn

back, but we won’t go very far ahead either – perhaps only a sparrow’s step.

And of course a lot of blood, an unprecedented

amount, will be shed.

(Maksim Gorky: Selected Letters, Oxford 1997)

Diary entry of Nicholas II

At night we

had to turn back from Malaia-Vichera as Liuban and Tosno turned out to be in

the hands of the insurgents. Shame and dishonour! It isn’t possible to get to

Tsarskoe, although all my thoughts and feelings are constantly there! How

difficult it must be for poor Alix to have to go through all this alone! Help

us, Lord!

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion, London 1996)

2 March

Letter from Alexandra to Nicholas

We all kiss

& kiss & bless you with without end. God will help & yr glory will

come. This is at the climax of the bad, the horror before our allies!! &

the enemies joy!! Can advise nothing, be only yr precious self. If you have to

give into things, God will help you to get out of them. Ah, my suffering saint,

I am one with you, inseparably one, old Wify. [P.S.] May this image I have

blessed bring you my fervent blessings, strength, help. Wear [Rasputin’s] cross

the whole time even if uncomfortable for my peace’s sake.

(The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra: April 1914-March 1917, ed. Joseph T. Fuhrmann, London 1999)

Telegram

from General Brusilov to Nicholas

…At the

present time only one measure can save the situation and make it possible to go

on fighting the external enemy, without which Russia will perish – that is to

abdicate from the throne in favour of his Majesty the Heir Tsarevich under the

regency of Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich. There is no other alternative. But

it is essential to make haste, to quell the popular conflagration which has

flared up and is gaining ever larger proportions, lest it entrain in its wake

immeasurably catastrophic consequences. Such an act will save the dynasty in

the person of the legitimate heir.

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion,London 1996)

Diary entry of

Nicholas II

Ruzsky came

in the morning and recited his long telephone conversation with Rodzianko.

According to him the situation in Petrograd is such that the ministry from the

Duma is now powerless to do anything because they are in conflict with the

Social Democrat party in the form of the workers’ committee. My abdication is

necessary. Ruzsky relayed his conversation to General Headquarters, and Alexeev

communicated it to all the commanders-in-chief. By 2.30 they had all sent their

answers, the essence of which is that for the sake of Russia’s salvation and in

order to maintain order at the front, this step has to be taken. I agreed. We

received a draft of the manifesto from Headquarters. In the evening Guchkov and

Shulgin arrived from Petrograd. I spoke with them and handed them the recopied

manifesto, signed. At 1 o’clock in the morning I left Pskov with a heavy heart.

All around only betrayal, cowardice and deceit!

(Nicholas and Alexandra: The Last Imperial Family of Tsarist Russia, London 1998)

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

The

Executive Committee of the Duma and the Council of Workmen’s and Soldiers’

Deputies have come to an agreement on the following points: 1. Abdication of

the Emperor; 2. Accession of the Tsarevich; 3. The Grand Duke Mikhail (the

Emperor’s brother) to be regent; 4. Formation of a responsible ministry; 5.

Election of a constituent assembly by universal suffrage; 6. All races to be

proclaimed equal before the law. The young deputy Kerensky, who has gained a

reputation as an advocate in political trials, is coming out as one of the most

active and strong-minded organisers of the new order.

(Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs 1914-1917, London 1973)

Diary entry of George V (King of England and cousin of Nicholas II)

[Grand

Duke] Michael came and I told him all about the revolution in Petrograd, he was

much upset, I fear Alicky

[Alexandra] is the cause of it all and Nicky has been

weak. Heard from Buchanan that the Duma had forced Nicky to sign his abdication

and Misha had been appointed Regent, and after he has been 23 years Emperor, I

am in despair.

(Sergei Mironenko, A Lifelong Passion,London 1996)

Speech by Alexander Kerensky in the Soviet of Workers' Deputies

Comrades, in joining the Provisional Government I remained what I was before - a republican (loud applause). In all my work I rely on the will of the people. I must have the powerful support of the people. Can I trust in you as in myself (rousing ovation, cries of 'we trust in you, comrade'). I cannot live without the people, and as soon as you begin to doubt me, kill me (new wave of applause) ... Comrades! Allow me to return to the Provisional Government and announce that I am joining its ranks with your agreement, as your representative (cries of 'Long live Kerensky').

(A.F. Kerensky, Diary of a Politician, Moscow 2007)

Report in The Times

There has been a revolution in Russia. The Emperor Nicholas II has abdicated. His brother, the Grand Duke Michael, has been appointed Regent. The Parliamentary leaders, with the people and the Army at their back, have carried out a coup d’Etat. While the bulk of the Petrograd garrison held the city for the Parliamentary cause, M. Rodzianko, the President of the Duma, demanded of the Tsar a new Government. Failing to receive satisfaction, M. Rodzianko placed himself at the head of a Provisional Government of 12 members. The new Government has dispersed the old Ministry, and has arrested many of its leading members … In Petrograd order is now being rapidly restored after considerable street fighting on Sunday and Monday. There is every indication that the revolution has completely succeeded.

(The Times, 'Revolution in Russia')

Diary entry of Georges-Maurice Paléologue, French Ambassador to Russia

Nicholas II

abdicated yesterday, shortly before midnight. When the emissaries of the Duma …

arrived at Pskov about nine o’clock in the evening [they said]…: ‘Nothing but the

abdication of Your Majesty in favour of your son can still save the Russian

Fatherland and preserve the dynasty.’ The Emperor replied very quickly, as if

referring to some perfectly commonplace matter: ‘I decided to abdicate

yesterday. But I cannot be separated from my son; that is more than I could

bear; his health is too delicate … I shall therefore abdicate in favour of my brother,

Michael Alexandrovitch’. … The Emperor then went into his study with the

Minister of the Court; he came out ten minutes later with the act of abdication

signed.

(Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs 1914-1917,

London 1973)

Diary entry of Nicholas II

It appears that Misha has abdicated. His manifesto concludes with a call for elections for a Constituent Assembly within six months. God knows who advised him to sign such a vile document! In Petrograd the disturbances have stopped - long may it remain that way.

(Nicholas and Alexandra: The Last Imperial Family of Tsarist Russia, London 1998)

4 March

Diary entry of Alexander Benois, artist and critic

An outstanding day in my personal life. I've left my 'safe little haven' and 'launched myself into the maelstrom'! I've been dragged into it by Grzhebin, Dobuzhinsky, Petrov-Vodkin and most of all by Gorky. I'd have preferred to remain an onlooker, on the side - everything that's going on makes me feel a little ill, it's all alien to me and I've started to see very clearly the earthly nature of things. But now I have no hope of coming to my senses, and it's too late to go back. On the other hand, the possibilities in front of me are not without a certain grandiosity! A sense of duty is also stirring in me. For it seems that much that can be done now in the specifically cultural sphere can only be done with my close participation and even leadership. I've put my shoulder to the wheel, even though I foresee that all the activity ahead will only lead to total disappointment! Ah, if only Diaghilev were here now! ... A gathering of us returned from Gorky's on this wonderfully keen frosty night .... There were quite a few pickets around burning fires. No cries or swearing anywhere. And absolutely no drunks (over the last few days there have been a lot, despite the prohibition on strong liquor). Generally there's a sense of unreality, as if it's a dream. And the question again arises: can the Russian people really be this wise and responsible? Or is this order just the expression of a general apathy and exhaustion? My own personal unease for some reason won't stop growing, without any real cause. Or am I only now beginning to make the transition from subconscious to conscious perception? Maybe this disquietude is that of the onlooker who has only seen the first act of a tragedy, the introduction, and is tormented by the thought: what will happen next?

(Alexander Benois, Diary 1916-1918, Moscow 2006)

On

Saturday, together with the other Allied Consular representative, I was present

at an impressive review on the Red Square where General Gruzinov, President of

the Moscow Zemstvo, took the march past of over 30,000 troops. The police had

wisely made themselves scarce. The people themselves kept order. Strangers

embraced in the streets and shouted ‘Long Live Liberty!’ Many educated Russians

who saw these scenes hoped and believed that something spiritual and almost

saintly, something inspiringly great, had happened in those days of March 1917.

From the defeat of despotism a better and stronger Russia would arise. Apart

from the unhappy reactionaries who had been imprisoned, there were in this

early period few Russians who realized that the peaceful revolution marked the collapse

of all discipline and that defeat – and something worse than defeat – now

stared a sorely tried people in the face. In the first 24 hours two things had

happened which were soon to destroy the initial unanimity of the

revolutionaries. First, the revolution had been made on the streets, for the

people had forestalled the cautious Duma composed of landowners, intellectuals

and professional men. The revolution had therefore two heads: the Duma and the

Soviets. The people had been led mainly by the Socialists. Yet in the new

Provisional Government there was only one Socialist, Alexander Kerensky, who

was then Minister of Justice. Secondly, in a country of which 80 percent of the

people were totally illiterate and which had been ruled autocratically for centuries,

all the freedoms were released at once. Among those freed from the jails were

not only political prisoners but also the worst criminals.

(Robert Bruce Lockhart, Foreign Affairs journal 1957)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

4 March 2017

In much that's been written about the centenary over the past few weeks, the first revolution - the February revolution that within the seven days of this week's post led to the overthrow of the monarchy - has been described as the 'forgotten revolution'. This was perhaps inevitable, given that the 'Great October Revolution' a few months later brought the communists to power and it was they who essentially wrote the script for the next eighty or so years. For Lenin and co, this was only the beginning, but by any measure it was an astonishing event. Britain's Brexit vote and America's election of its first citizen-president that fill today's column inches are painted in vivid colours, but a coup that ended several centuries of autocratic government by monarchy and replaced it initially with rule by parliament was more significant by far. And yet, reading the diary of Nicholas or his letters to his 'wify' over these transition days, one would think that he was being asked to relinquish a rather tiresome desk job, one that he had clung to more out of habit than aptitude (which is perhaps not far from the truth). David Reynolds, writing in the New Statesman about a new book by Robert Service, The Last of the Tsars, talks of 'the tsar's limp surrender of the throne' and gives these possible explanations: 'Emotional exhaustion; pressure from the army command; concern for his haemophiliac son; the impossibility of squaring a constitutional monarchy with his coronation oath.' From some of the first-hand testimony quoted above, it's hard to disagree with his conclusion, that 'it still seems astonishing that this proud scion of the Romanov dynasty, rulers of Russia for three centuries, signed away his throne on a provincial railway station with blank calm - as if, to quote one aide, "he were turning over command of a cavalry squadron".'

8 October

Letter from Lenin to the Bolshevik Comrades attending the Regional Congress of

the Soviets of the Northern Region

Comrades, Our revolution is passing through a highly critical period …

A gigantic task is being imposed upon the responsible leaders of our Party,

failure to perform which will involve the danger of a total collapse of the

internationalist proletarian movement. The situation is such that verily,

procrastination is like unto death … In the vicinity of Petrograd and in

Petrograd itself — that is where the insurrection can, and must, be decided on

and effected … The fleet, Kronstadt, Viborg, Reval, can and must advance

on Petrograd; they must smash the Kornilov regiments, rouse both the capitals,

start a mass agitation for a government which will immediately give the land to

the peasants and immediately make proposals for peace, and must overthrow

Kerensky’s government and establish such a government. Verily, procrastination

is like unto death.

(V.I. Lenin and Joseph Stalin, The Russian Revolution: Writings and Speeches

from the February Revolution to the October Revolution, 1917, London 1938)

9 October

Report in The Times

The Maximalist [Bolshevik], M. Trotsky, President of the Petrograd Soviet,

made a violent attack on the Government, describing it as irresponsible and

assailing its bourgeois elements, ‘who,’ he continued, ‘by their attitude are

causing insurrection among the peasants, increasing disorganisation and trying

to render the Constituent Assembly abortive.’ ‘The Maximalists,’ he declared,

‘cannot work with the Government or with the Preliminary Parliament, which I am

leaving in order to say to the workmen, soldiers, and peasants that Petrograd,

the Revolution, and the people are in danger.’ The Maximalists then left the

Chamber, shouting, ‘Long live a democratic and honourable peace! Long live the

Constituent Assembly!’

(‘Opening of Preliminary Parliament’, The Times)

10 October

As Sukhanov left his home for the Soviet on the morning of the 10th, his

wife Galina Flakserman eyed nasty skies and made him promise not to try to

return that night, but to stay at his office … Unlike her diarist husband,

who was previously an independent and had recently joined the Menshevik left,

Galina Flakserman was a long-time Bolshevik activist, on the staff of Izvestia.

Unbeknownst to him, she had quietly informed her comrades that comings and

goings at her roomy, many-entranced apartment would be unlikely to draw

attention. Thus, with her husband out of the way, the Bolshevik CC came

visiting. At least twelve of the twenty-one-committee were there … There

entered a clean-shaven, bespectacled, grey-haired man, ‘every bit like a

Lutheran minister’, Alexandra Kollontai remembered. The CC stared at the

newcomer. Absent-mindedly, he doffed his wig like a hat, to reveal a familiar

bald pate. Lenin had arrived.

(China Miéville, October: The Story of the Russian Revolution, London 2017)

Memoir by the Menshevik Nikolai

Sukhanov

Oh, the novel jokes of the merry muse of History! This supreme and decisive

session took place in my own home … without my knowledge … For such a

cardinal session not only did people come from Moscow, but the Lord of Hosts

himself, with his henchman, crept out of the underground. Lenin appeared in a

wig, but without his beard. Zinoviev appeared with a beard, but without his

shock of hair. The meeting went on for about ten hours, until about 3 o’clock

in the morning … However, I don’t actually know much about the exact

course of this meeting, or even about its outcome. It’s clear that the question

of an uprising was put … It was decided to begin the uprising as quickly

as possible, depending on circumstances but not on the Congress.

(N.N. Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917: a Personal Record, Oxford 1955)

11 October

British Consul Arthur Woodhouse in a letter home

Things are coming to a pretty pass here. I confess I should like to be out

of it, but this is not the time to show the white feather. I could not ask for

leave now, no matter how imminent the danger. There are over 1,000 Britishers

here still, and I and my staff may be of use and assistance to them in an

emergency.

(Helen Rappaport, Caught in the Revolution: Petrograd 1917, London 2017)

Memoir of Fedor Raskolnikov, naval

cadet at Kronstadt

The proximity of a proletarian rising in Russia, as prologue to the world

socialist revolution, became the subject of all our discussions in

prison … Even behind bars, in a stuffy, stagnant cell, we felt instinctively

that the superficial calm that outwardly seemed to prevail presaged an

approaching storm … At last, on October 11, my turn [for release]

came … Stepping out of the prison on to the Vyborg-Side embankment and

breathing in deeply the cool evening breeze that blew from the river, I felt

that joyous sense of freedom which is known only to those who have learnt to

value it while behind bards. I took a tram at the Finland Station and quickly

reached Smolny … In the mood of the delegates to the Congress of Soviets

of the Northern Region which was taking place at that time .. an unusual

elation, an extreme animation was noticeable … They told me straightaway

that the CC had decided on armed insurrection. But there was a group of

comrades, headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev, who did not agree with this decision

and regarded a rising a premature and doomed to defeat.

(F.F. Raskolnikov, Kronstadt and Petrograd in 1917, New York 1982, first

published 1925)

12 October

Sir George Buchanan, British Ambassador to Russia

On [Kerensky] expressing the fear that there was a strong anti-Russian

feeling both in England and France, I said that though the British public was

ready to make allowances for her difficulties, it was but natural that they

should, after the fall of Riga, have abandoned all hope of her continuing to

take an active part in the war … Bolshevism was at the root of all the

evils from which Russia was suffering, and if he would but eradicate it he

would go down to history, not only as the leading figure of the revolution, but

as the saviour of his country. Kerensky admitted the truth of what I had said,

but contended that he could not do this unless the Bolsheviks themselves

provoked the intervention of the Government by an armed uprising.

(Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia, London 1923)

13 October

Diary entry of Louis de Robien, attaché at the French Embassy

Kerensky is becoming more and more unpopular, in spite of certain grotesque

demonstrations such as this one: the inhabitants of a district in Central

Russia have asked him to take over the supreme religious power, and want to

make him into a kind of Pope as well as a dictator, whereas even the Tsar was

really neither one nor the other. Nobody takes him seriously, except in the

Embassy. A rather amusing sonnet about him has appeared, dedicated to the beds

in the Winter Palace, and complaining that they are reserved for hysteria

cases … for Alexander Feodorovich (Kerensky’s first names) and then

Alexandra Feodorovna (the Empress).

(Louis de Robien, The Diary of a Diplomat in Russia 1917–1918, London 1969)

14 October 2017

The BBC2 semi-dramatisation of how the Bolsheviks took power, shown this week,

was a curious thing. Talking heads in the form of Figes, Mieville, Rappaport,

Sebag-Montefiore, Tariq Ali, Martin Amis and others were interspersed with

moody reconstructions of late-night meetings, and dramatic moments such as

Lenin’s unbearded return to the Bolshevik CC (cf Sukhanov above). The programme

felt rather staged and unconvincing, with a lot of agonised expressions and

fist-clenching by Lenin, but the reviewers liked it. Odd, though, that

Eisenstein’s storming of the Winter Palace is rolled out every time, with a

brief disclaimer that it’s a work of fiction and yet somehow presented as

historical footage. There’s a sense of directorial sleight of hand, as if the

rather prosaic taking of the palace desperately needs a re-write. In some

supra-historical way, Eisenstein’s version has become the accepted version.

John Reed’s Ten Days that Shook the World

, currently being

serialised on Radio 4, is also presented with tremendous vigour, and properly

so as the book is nothing if not dramatic. Historical truth, though, is often

as elusive in a book that was originally published — in 1919 — with an

introduction by Lenin. ‘Reed was not’, writes one reviewer, ‘an ideal observer.

He knew little Russian, his grasp of events was sometimes shaky, and his facts

were often suspect.’ Still, that puts him in good company, and Reed is

undoubtedly a good read.